Reina SofÍa University Hospital

Cordoba, Spain

The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine

Medical Director Division of Gastroenterology and Hepatology

Clinical Director, IBD Center

Johns Hopkins Sibley Memorial Hospital

Washington, DC

@DCharabaty

Reina SofÍa University Hospital

IMIBIC, University of Cordoba

Cordoba, Spain

Extraintestinal manifestations (EIMs) are common in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). They usually appear during the course of IBD, but in 25% of cases, they precede or are concurrent with IBD diagnosis.1,2 The most common EIMs are IBD-associated spondyloarthropathies (SpAs), which occur in almost one-third of patients during their IBD course, and are classified as axial SpA or peripheral SpA, which includes arthritis, dactylitis or “sausage fingers,” and enthesitis or inflammation at the bony insertion sites of ligaments, tendons, and

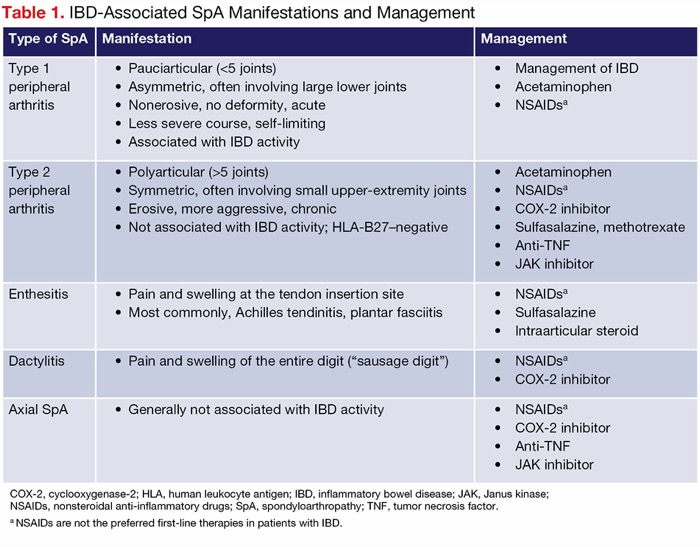

IBD-associated SpAs can parallel disease activity or be independent of luminal inflammation (Table 1) and often worsen the patient’s quality of life. SpAs require a multidisciplinary management approach that includes a rheumatologist, radiologist, physiotherapist, and, in many cases, a psychologist.3,4

| Table 1. IBD-Associated SpA Manifestations and Management | ||

| Type of SpA | Manifestation | Management |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 peripheral arthritis |

|

|

| Type 2 peripheral arthritis |

|

|

| Enthesitis |

|

|

| Dactylitis |

|

|

| Axial SpA |

|

|

| COX-2, cyclooxygenase-2; HLA, human leukocyte antigen; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; JAK, Janus kinase; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; SpA, spondyloarthropathy; TNF, tumor necrosis factor. a NSAIDs are not the preferred first-line therapies in patients with IBD. | ||

Peripheral arthritis, the most frequent type of IBD-related SpA, can be subclassified into type 1, which involves less than 5 joints (pauciarticular), typically the large joints of the lower extremities, and closely follows the course of IBD activity (SpA flares coincide with IBD flares and resolve when luminal disease is in remission). Type 2 involves more than 5 joints (polyarticular), often the smaller joints of the hands symmetrically, and follows a chronic course independent of IBD activity.5

Axial SpA is less common, with a prevalence of 10% to 20% in patients with IBD.3 It involves inflammation of the sacroiliac joints, or sacroiliitis, which often is asymptomatic but can manifest as buttock pain, inflammatory back pain, and ankylosing spondylitis (AS). Inflammatory back pain is defined as back pain for longer than 3 months that is exacerbated by rest—often waking up the patient at night or present in the early morning—and is improved with physical activity. AS, which manifests as inflammatory back pain with radiographic evidence of sacroiliitis and spinal inflammation, can progress to spinal fusion (bamboo spine), leading to limitation of lumbar motion in both frontal and sagittal planes and limitation of chest expansion.6 In the United States, the genetic marker HLA-B27 is found in most White but only 50% of Black patients with AS.7

In this article, we summarize an @MondayNightIBD case conversation that focused on the management of a patient with IBD and peripheral SpA and explore factors to consider in treatment decisions based on the available data and expert opinions. We review the efficacy and safety data of therapies with varying mechanisms of action (MOAs) that can treat both luminal and joint disease.

Clinical Scenario

A 35-year-old woman with ulcerative colitis (UC) who has been in remission on infliximab (IFX) for the last 3 years developed a moderate/severe flare and was found to have high levels of anti-IFX antibodies. Her therapy was changed to ustekinumab (Stelara, Johnson & Johnson), which led to UC remission. However, the patient now complains of pain in both hands and knees, mainly in the morning, that partially improves with activity. The pain is limiting her ability to grasp objects, hindering her work as a hairdresser. There is a 4-month wait until she can be seen by a rheumatologist. The @MondayNightIBD gastroenterologists and health professionals were polled on what they would do next.

Case Discussion

The discussion focused on the differential diagnosis of peripheral arthritis in a patient with IBD; treatment options for IBD-associated peripheral SpA; and personalizing treatment choice based on disease and patient details, including the burden of her joint pain on her daily activities and work; short-term pain relief and long-term treatment plan; and the safety of different MOAs in pregnancy in a woman of childbearing age.

Differential Diagnosis of Peripheral Arthritis With IBD

There is no specific test to diagnose IBD-associated peripheral SpA, but a thorough history, physical exam that reveals joint swelling, tenderness to palpation, dysaesthesia, and redness, as well as judicious use of tests to rule out other causes of arthritis (inflammatory, infectious, or systemic conditions) can lead to the diagnosis.

Common inflammatory conditions can be associated with IBD and cause arthritis, such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and psoriatic arthritis.8,9 Crystal arthropathies, such as gout, also may arise due to metabolic changes associated with IBD. Systemic autoimmune diseases, including systemic lupus erythematosus and Sjogren’s syndrome, often affect the joints but have distinct clinical and serologic markers. Infectious causes, such as septic arthritis or reactive arthritis following an infectious enterocolitis, also should be considered.

Delayed serum sickness–like reactions have been reported in patients who receive IFX and have developed anti-IFX antibodies; the activation of complement by antigen (IFX)-antibody immune complexes deposited in blood vessels, skin, and joint tissue leads to arthritis and pain in large joints and typically the jaw, and can cause urticaria, fever, lymphadenopathy, and rarely, glomerulonephritis. These types of reactions have not been reported with newer MOAs that have a low incidence of anti-drug antibodies.10 Drug-induced lupus has been reported primarily with anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) agents and can present with arthritis with a malar rash, and occasionally can lead to serious lupus complications.11 Finally, several clinicians reported that in their clinical practice they have occasionally observed new-onset arthralgias or arthritis in IBD patients after stopping anti-TNF therapy, suggesting that anti-TNFs mask IBD-associated SpA that can become symptomatic when IBD treatment is changed to a different MOA that doesn’t target joint disease.12

Treatment of IBD-Associated Peripheral SpA

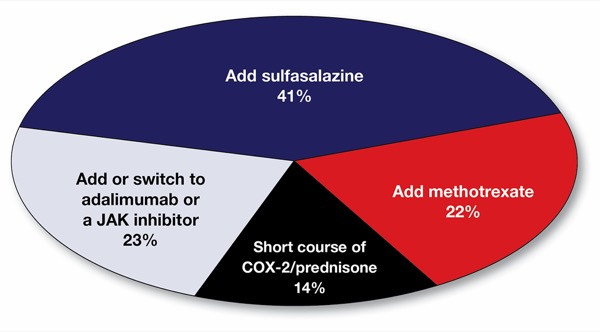

In the case presented, in which ustekinumab is controlling the luminal UC activity but not the peripheral arthritis, clinicians evaluated the options of adding a short course of an anti-inflammatory agent (eg, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs], selective cyclooxygenase-2 [COX-2] inhibitor, prednisone); adding a conventional antirheumatic drug such as sulfasalazine or methotrexate; adding another advanced therapy; or switching the IBD therapy altogether from an anti-interleukin (IL) 12/23p40 to a drug with an MOA that can co-treat the luminal and the joint disease, such as an anti-TNF agent or a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor.

Take-Home Points

- Ask your patients with IBD about joint pain at diagnosis and periodically during the disease course. SpAs and arthralgias are the most common EIMs in IBD, and they negatively affect daily and work activities, as well as patients’ quality of life.

- Involve a rheumatologist early in the diagnostic and therapeutic process.

- The differential diagnosis of peripheral arthritis in IBD includes drug reactions, infectious or post-infection reaction, and concomitant rheumatologic disease.

- When IBD and SpA coexist at diagnosis, choose a therapy that co-treats the luminal and joint disease. Although type 1 peripheral SpA usually responds to any MOA that controls the luminal inflammation, type 2 (and some type 1) peripheral and axial SpAs are best treated with a therapy that co-treats IBD and SpA, such as an anti–TNF agent or a JAK inhibitor.

- When SpA manifests later in the course of IBD, tailor treatment strategies according to IBD activity, severity of SpA symptoms, and current use/efficacy of an advanced therapy.

- Initial management of SpA includes anti-inflammatory agents, such as a COX-2 inhibitor or prednisone; physical therapy; and lifestyle changes. Sulfasalazine and methotrexate can be effective for peripheral SpA. Anti-TNF therapies and JAK inhibitors are effective for peripheral and axial SpA.

- Decision-making should be personalized and shared. Consider disease course and patient factors such as occupation, pregnancy planning, other EIMs, and preferences in management strategy.

Acute management. COX-2 inhibitors, such as celecoxib (Celebrex, Pfizer) at a dose of 100 mg twice daily, are effective for arthritis and have a lower risk for GI toxicities than nonselective NSAIDs.13,14 However, their safety in IBD patients is not well established, and long-term use may still pose risks. NSAIDs are first-line therapies for different types of arthritis due to their low cost and high efficacy. Rheumatologists often use naproxen at doses of 375 to 500 mg twice daily. However, NSAID use in the IBD population is limited because of their potential risk of triggering an IBD flare by increasing mucosal permeability and exposure to luminal antigens and toxins. Although several retrospective studies suggested an association between NSAID use and IBD flares, a recent meta-analysis did not find a consistent association.15 In addition, the largest study on NSAIDs and IBD exacerbation could not confirm an association between IBD flare and NSAID exposure within 2 weeks to 6 months after exposure after adjusting for confounders.16 Alternatively, a short course of prednisone, starting at a low dose of 20 mg per day tapered over 2 weeks, can provide fast relief from arthritis and pain.

Conventional antirheumatic drugs. Although mesalamine products are used more commonly because they are better tolerated, sulfasalazine (unlike mesalamine) is effective for treating peripheral SpAs as well as mild/moderate UC.12,14 Clinical studies have shown that sulfasalazine at a dose of 2 to 3 g daily can improve peripheral SpA symptoms in IBD patients, leading to a significant decrease in morning stiffness, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and the daily NSAID dose.17 It is best to start sulfasalazine at a low dose (500 mg twice per day) to prevent GI side effects, increasing the dose progressively every 2 weeks; supplementation also is recommended with 1 mg daily of folic acid and checking blood cell counts after the first 4 to 8 weeks of initiation also is recommended to monitor for the rare side effect of agranulocytosis. Sulfasalazine is safe during pregnancy, but because it inhibits folic acid absorption, high-dose supplementation with 2 to 5 mg daily of folic acid is recommended from 3 months before conception through pregnancy in women taking sulfasalazine.

Although methotrexate is not effective as monotherapy in treating UC,15,16 it often is used by rheumatologists in the management of peripheral SpAs. The typical dose is 15 mg weekly, which can be escalated by 5 mg per month to 25 to 30 mg weekly or the highest tolerable and lowest effective dose. In the case of nonresponse, a switch to subcutaneous methotrexate can lead to increased efficacy, Again, it is important to monitor blood cell counts and liver enzymes and supplement folic acid at a dose of 1 mg per day or 5 mg per week. However, it is important to discuss with women of childbearing age that methotrexate is an abortifacient that can lead to congenital malformations if used during conception and pregnancy. Women of childbearing age should use an effective contraceptive method while taking methotrexate, and the drug should be stopped at least 3 months prior to conception.

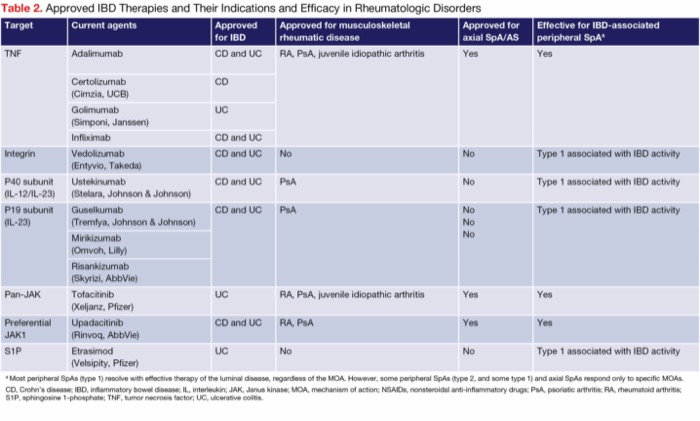

Advanced therapies to target luminal and joint disease. Adding another advanced therapy to ustekinumab to treat the joint disease (dual advanced therapy) or switching to an MOA that treats both IBD and arthritis are each reasonable options (Table 2). The 2 drug classes with MOAs that have been shown to be effective for IBD as well as peripheral and axial SpAs are the anti-TNF agents and JAK inhibitors. Adalimumab and infliximab are the most used anti-TNF agents in this setting; they are approved for axial SpAs, AS, RA, and psoriatic arthritis and have been shown to be effective for IBD-associated peripheral SpAs. Although ustekinumab (IL-12/23p40 inhibitor) is approved for psoriatic arthritis, its efficacy in the treatment of peripheral and axial SpAs is limited. Similarly, IL-23p19 inhibitors such as risankizumab (Skyrizi, AbbVie) and guselkumab (Tremfya, Johnson & Johnson) also are approved for psoriatic arthritis, but there are limited data on their efficacy for IBD-associated SpAs.18,19 In the JAK inhibitor family, tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Pfizer) and upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) are approved for axial SpAs, RA, and psoriatic arthritis, and are clinically effective for IBD-associated peripheral SpAs.20-23

| Table 2. Approved IBD Therapies and Their Indications and Efficacy in Rheumatologic Disorders | |||||

| Target | Current agents | Approved for IBD | Approved for musculo- skeletal rheumatic disease | Approved for axial SpA/AS | Effective for IBD-associated peripheral SpAa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF | Adalimumab | CD and UC | RA, PsA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Yes | Yes |

| Certolizumab (Cimzia, UCB) | CD | ||||

| Golimumab (Simponi, Janssen) | UC | ||||

| Infliximab | CD and UC | ||||

| Integrin | Vedolizumab (Entyvio, Takeda) | CD and UC | No | No | Type 1 associated with IBD activity |

| P40 subunit (IL-12/IL-23) | Ustekinumab (Stelara, Johnson & Johnson) | CD and UC | PsA | No | Type 1 associated with IBD activity |

| P19 subunit (IL-23) | Guselkumab (Tremfya, Johnson & Johnson) | CD and UC | PsA | No | Type 1 associated with IBD activity |

| Mirikizumab (Omvoh, Lilly) | |||||

| Risankizumab (Skyrizi, AbbVie) | |||||

| Pan-JAK | Tofacitinib (Xeljanz, Pfizer) | UC | RA, PsA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis | Yes | Yes |

| Preferential JAK1 | Upadacitinib (Rinvoq, AbbVie) | CD and UC | RA, PsA | Yes | Yes |

| S1P | Etrasimod (Velsipity, Pfizer) | UC | No | No | Type 1 associated with IBD activity |

| a Most peripheral SpAs (type 1) resolve with effective therapy of the luminal disease, regardless of the MOA. However, some peripheral SpAs (type 2, and some type 1) and axial SpAs respond only to specific MOAs. CD, Crohn’s disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; IL, interleukin; JAK, Janus kinase; MOA, mechanism of action; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; PsA, psoriatic arthritis; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; S1P, sphingosine 1-phosphate; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; UC, ulcerative colitis. | |||||

Lifestyle changes. Finally, regardless of the medical therapy plan, it is important to include lifestyle changes. Low-impact exercises and/or physical therapy can improve joint function and reduce pain and stiffness. Smoking cessation can improve the outcome and response to therapy for EIM, and an IBD anti-inflammatory diet that limits ultra-processed foods and prioritizes fruit, vegetables, legumes, nuts , healthy fats, and lean protein can improve overall patient well-being.

Personalized Management Based On Disease and Patient Factors

The rationale for a short course of an anti-inflammatory agent is to provide fast and effective relief for joint pain in a patient whose ability to work is impeded by peripheral arthritis. Most @MondayNightIBD participants reported being comfortable using a short course of NSAIDs or a COX-2 inhibitor in a patient in endoscopic remission. This short-term management is a good option to consider while waiting for the patient to be seen by rheumatology or for the effective dose of sulfasalazine or methotrexate to be achieved or another advanced therapy to be approved.

Several participants in our #MondayNightIBD discussion reported experiencing limited efficacy of sulfasalazine or methotrexate in controlling SpAs, so it is important to discuss adding or switching to an effective advanced therapy, either as an initial strategy or if a conservative approach is not tolerated or effective. An initial strategy of switching from ustekinumab to a different MOA that co-treats both the luminal and joint disease is more likely to be considered if the current advanced therapy is not controlling the luminal disease. In this patient, whose UC is in remission on ustekinumab, the rationale for maintaining ustekinumab and adding a second agent—whether sulfasalazine, methotrexate, or a second advanced therapy, such as an anti-TNF drug or a JAK inhibitor—to treat the SpA stems from the legitimate concern that switching to a new advanced therapy altogether poses a risk of non-response to the new MOA and an IBD flare.

Indeed, because most therapies have a therapeutic ceiling of 30% to 50% for disease remission, there is no guarantee that the luminal disease currently in remission on ustekinumab would respond to a different MOA. We also know from trials leading to approval of IBD drugs that patients who have been exposed to more than one advanced therapy, in particular to an anti-TNF therapy, often have lower response to a new agent than bio-naive patients would have. Therefore, it is reasonable to consider dual advanced therapy if conservative management is unsuccessful. The main concern with this strategy is the potential increased risk for serious events, mainly infectious complications.

A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies reporting on dual advanced therapies (2 biologics or 1 biologic and 1 small-molecule therapy) for either refractory IBD or IBD with concurrent EIM showed that this strategy is effective and generally safe, with a pooled rate of 6% for serious adverse events.24

One strategy is to add a second advanced therapy to ustekinumab and once the peripheral SpA is in remission, stop ustekinumab and keep the patient on the monotherapy that co-treats the IBD and SpA, while closely monitoring for IBD relapse according to inflammatory markers such as fecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein, endoscopic assessment, and clinical symptoms.

Finally, when selecting a therapy for women of childbearing age, it is important to consider whether the patient has plans for pregnancy in the near to medium future or if she is able and willing to use an effective contraceptive method, recognizing that methotrexate and JAK inhibitors are contraindicated during conception, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Finally, the patient’s preferences for the agent’s method of delivery and safety and efficacy profile need to be discussed for effective shared decision-making.

Conclusion

IBD-associated SpAs add a significant comorbidity to IBD and often have a negative impact on patients’ daily and work activities and overall quality of life. SpA deserves careful assessment and multidisciplinary management. Before choosing an IBD therapy, gastroenterologists should inquire about the presence of EIMs—particularly SpA—and choose an MOA that preferentially co-treats the luminal and joint disease when possible. If SpA becomes symptomatic, management and treatment choices should take into account whether the luminal disease is in remission on current therapy, whether the patient is already taking an advanced therapy, and whether short-term use of anti-inflammatory agents is effective or a long-term drug therapy strategy is needed.

References

- Algaba A, Guerra I, Ricart E, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: study based on the ENEIDA Registry. Dig Dis Sci. 2021;66(6):2014-2023.

- Kilic Y, Kamal S, Jaffar F, et al. Prevalence of extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2024;30(2):230-239.

- Gordon H, Burisch J, Ellul P, et al. ECCO guidelines on extraintestinal manifestations in inflammatory bowel disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(1):1-37.

- Vavricka SR, Schoepfer A, Scharl M, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(8):1982-1992.

- Rogler G, Singh A, Kavanaugh A, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease: current concepts, treatment, and implications for disease management. Gastroenterology. 2021;161(4):1118-1132.

- Salvarani C, Fries W. Clinical features and epidemiology of spondyloarthritides associated with inflammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15(20):2449.

- Khan MA, Braun WE, Kushner I, et al. HLA B27 in ankylosing spondylitis: differences in frequency and relative risk in American Blacks and Caucasians. J Rheumatol. 2023;50(1):39-43.

- Freuer D, Linseisen J, Meisinger C. Association between inflammatory bowel disease and both psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158(11):1262.

- Ono K, Kishimoto M, Deshpande GA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients with spondyloarthritis and inflammatory bowel disease versus inflammatory bowel disease-related arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 2022;42(10):1751-1766.

- Ghosh S, Feagan BG, Ott E, et al. Safety of ustekinumab in inflammatory bowel disease: pooled safety analysis through 5 years in Crohn’s disease and 4 years in ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2024;18(7):1091-1101.

- Almoallim H. Anti-tumor necrosis factor-a induced systemic lupus erythematosus. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6(1):315-319.

- Diaz LI, Keihanian T, Schwartz I, et al. Vedolizumab-induced de novo extraintestinal manifestations. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y). 2020;16(2):75-81.

- Kvasnovsky CL, Aujla U, Bjarnason I. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and exacerbations of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50(3):255-263.

- Kefalakes H, Stylianides TJ, Amanakis G, et al. Exacerbation of inflammatory bowel diseases associated with the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs: myth or reality? Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65(10):963-970.

- Moninuola OO, Milligan W, Lochhead P, et al. Systematic review with meta- analysis: association between acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and risk of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis exacerbation. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;47(11):1428-1439.

- Cohen-Mekelburg S, Van T, Wallace B, et al. The association between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use and inflammatory bowel disease exacerbations: a true association or residual bias? Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(11):1851-1857.

- Dougados M, Maetzel A, Mijiyawa M, et al. Evaluation of sulphasalazine in the treatment of spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1992;51(8):955-958.

- Louis E, Schreiber S, Panaccione R, et al. Risankizumab for ulcerative colitis: two randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 2024;332(11):881-897.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Chapman JC, Colombel JF, et al. Risankizumab versus ustekinumab for moderate-to-severe Crohn’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2024;391(3):213-223.

- Cozzi G, Scagnellato L, Lorenzin M, et al. Spondyloarthritis with inflammatory bowel disease: the latest on biologic and targeted therapies. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2023;19(8):503-518.

- Suzuki K, Akiyama M, Inokuchi H, et al. Successful treatment of Crohn’s disease-related peripheral spondyloarthritis with upadacitinib: two case reports and case-based review. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44(12):3127-3133.

- Vavricka SR, Gubler M, Gantenbein C, et al. Anti-TNF treatment for extraintestinal manifestations of inflammatory bowel disease in the Swiss IBD cohort study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(7):1174-1181.

- Greuter T, Bertoldo F, Rechner R, et al. Extraintestinal manifestations of pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017;65(2):200-206.

- Ahmed W, Galati J, Kumar A, et al. Dual biologic or small molecule therapy for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):e361-e379.

This article is from the June 2025 print issue.