The American College of Gastroenterology published a newly updated guideline on the diagnosis and management of eosinophilic esophagitis (Am J Gastroenterol 2025;120[1]:31-59). GEN’s Sarah Tilyou spoke with lead author Evan S. Dellon, MD, MPH, a professor of medicine and the director of the Center for Esophageal Disease and Swallowing at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill School of Medicine, about the guideline and its implications for GI practice.

GEN: What prompted the guideline?

Dr. Dellon: The 2013 ACG guideline had incorporated data up until 2011-2012, so there was a clear need to update the guideline because of the bulk of information developed in the field since then. This includes updated diagnostic guidelines, new treatments, including two FDA-approved agents (dupilumab [Dupixent, Sanofi/Regeneron] and budesonide [Eohilia, Takeda]), and new ways to assess disease outcomes. There have been other guidelines since then, including one from the American Gastroenterological Association in 2020, and, interestingly, many countries are coming out with their own guidelines. European guidelines also are being updated.

GEN: Are there any differences between other guidelines and this one?

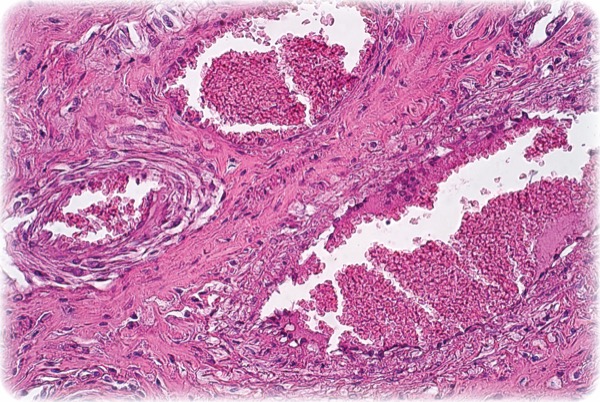

Dr. Dellon: There are some differences but also some similarities. We divided this guideline into diagnosis and management. The new diagnostic recommendations echo those in the 2018 consensus conference (Gastroenterology 2018;155[4]:1022-1033). This is something we did throughout this process. If there was a strong guideline that didn’t need to be changed, we would emphasize and refer to it, but we didn’t change the basic tenets. So, the diagnostic guidelines are pretty much the same, where you need to have symptoms of esophageal dysfunction, at least 15 eosinophils per high-power field, and exclusion of other potential causes of esophageal eosinophilia, to diagnose EoE.

Overall, the guideline includes 19 recommendations, as well as 25 or so key concepts. The key concepts relate to instances where there were not enough data to make an evidence-based recommendation, but we could provide additional practical guidance and help give some color to the recommendation statements. For example, for diagnosis, there’s an emphasis on thinking about the clinical context that would increase the suspicion for EoE diagnosis or detect subtle symptoms (the so-called avoidance and modification behaviors). There’s a recommendation about assessing the endoscopic appearance with the EoE Endoscopic Reference Score (EREFS). There’s a reemphasis on the correct biopsy protocol and having pathologists quantify the eosinophil count. There’s also an emphasis on performing endoscopy with patients not on dietary elimination or proton pump inhibitors, which could potentially confound the diagnosis by giving a falsely normal exam. We also included information about using the new Index of Severity for Eosinophilic Esophagitis (I-SEE) to help characterize disease severity at baseline.

GEN: What’s new that clinicians need to know?

Dr. Dellon: There are quite a few things that are new.

For treatments, for the first time, this guideline recommends a biologic for treatment of EoE: the FDA-approved agent dupilumab. Because these are evidence-based guidelines, the recommendation is in line with the data in the approval studies. For example, dupilumab is a recommended therapy in patients from age 1 to 11 years and in those 12 years and older who are nonresponsive to PPI therapy. This is because every patient in those studies was a PPI nonresponder. In general, dupilumab is positioned as a step-up therapy, but there are times when you can consider using it earlier. That’s a message that’s consistent with a previous consensus statement that came out a year or two ago (Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2023;130[3]:371-378).

In terms of the overall treatment algorithm, there is a new concept related to thinking about selecting an anti-inflammatory therapy—whether that’s diet, PPIs, steroids or a biologic—but doing that in parallel with assessing for whether there is fibrostenosis because to focus on one thing alone results in an inadequate treatment approach for patients. For example, if you’re only looking at strictures and dilating them but not treating the underlying disease, you’re not going to get a good response and strictures will recur. And if you’re only doing an anti-inflammatory therapy and not reassessing endoscopically, patients may not feel better if there are persistent strictures. That’s a new way of thinking that’s presented in an updated treatment algorithm that hopefully can be helpful for providers.

There’s also an emphasis on the concept that EoE is chronic and requires maintenance therapy, with specific recommendations on assessment of symptoms, endoscopy and histology after patients start treatment, after changing treatment, and during the long-term follow-up. Again, that’s consistent with prior published monitoring statements from a joint U.S. and European group (Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2023;21[10]:2526-2533). Also, for the first time in an EoE guideline, there are pediatric-specific considerations.

GEN: How might the new guideline change practice?

Dr. Dellon: It hopefully will change practice by providing a more consistent approach to diagnosis and treatment, with an emphasis on choosing one treatment up front—not doing combination therapy initially—and assessing whether that treatment works, changing treatments if necessary in initial nonresponders, and then reassessing in a more formal process and establishing long-term follow-up.

It should also change things in terms of the pediatric-specific recommendations, where there is a suggestion to do an esophagram in some children with dysphagia before endoscopy. This is to help understand if a child may need a dilation, which is generally a more involved procedure in pediatrics than it is in adults. In addition, there is a recommendation to think about whether feeding therapy is needed in a child. Again, it’s adjunctive and not usually thought about in adults, but formalizing that kind of pathway for children is important.

GEN: What were some of the hottest points of debate among the guideline panel, and how did you resolve them?

Dr. Dellon: It was an interesting process. These are evidence-based guidelines. We had two methodologists in our multidisciplinary group of adult and pediatric gastroenterologists and an allergist. When we were formulating our questions for our evidence review, we started pretty specifically, and then we had to see what kind of data there were to inform the recommendations and, from there, refine our questions and statements.

So, there were some debates. For example, our recommendation on topical steroids is very general. It just says to use topical steroids. It doesn’t split that by pediatrics or adults or by the specific formulation. Because of that, the evidence overall is a little bit weaker than you might expect, even though this class of medications has an extensive evidence base with multiple randomized trials. When all ages and medication types are grouped, you have to account for not so many trials in children, not so many trials with the newer esophageal-specific formulations and a lot of heterogeneity between the previous trials.

We also had some questions related to the biologic recommendations. Do we keep the two recommendations separate (one for adolescents/adults and one for children) to directly mirror the trials, which is what happened, or do we try to do a similar combined recommendation? Then, there was the question of where we position these medications in the treatment algorithm because there are no comparative efficacy trials. So that also led to some debates.

GEN: What are the biggest remaining gaps in evidence?

Dr. Dellon: I think the biggest one is the lack of comparative efficacy data between different EoE treatments. We don’t have data on PPIs versus steroids using optimized doses or the EoE-specific formulations. We don’t have data on steroids versus biologics. We don’t have data on steroids versus diet or PPIs versus diet. Therefore, this is an area where we’re selecting treatment based on shared decision-making and patient and provider perspectives.

Another important area is the population best suited for biologics. The current studies generally include treatment-refractory patients with long-standing EoE. We don’t have data on using biologics in newly diagnosed patients. By the same token, the studies may exclude the most severe patients who need frequent dilation. So that’s another group for whom we don’t have data. Studying these populations would be very useful.

The next big category is personalization of therapy with targeted therapies. Because we see heterogeneous responses in trials to date, it is likely that there are patient-specific factors or biomarkers that could direct therapies to the patients who are most likely to respond to them. Similarly, we don’t have noninvasive biomarkers and have to do endoscopy frequently to assess response in patients with EoE. It would be very helpful to combine predictive biomarkers with personalized treatments, so we could know who is most likely to respond to one of these more advanced treatments and then follow them noninvasively.

Last, there are small molecules that are being tested that might be appropriate for newly diagnosed first-line patients. The mechanism and safety profile of the drug often will dictate which group of patients you might use them in. I think we’ll see trials for some of these agents that are targeting different populations in addition to the refractory patients.

GEN: Since there aren’t that many pediatric GI practitioners, do you have any advice for general gastroenterologists treating EoE in both children and adults?

Dr. Dellon: It’s a great point that there aren’t a ton of specialists. In practice, there are a couple of issues with that. The first, for established pediatric patients, is making a successful transition to adult care, and that’s a real gap we have now. The second is, for all patients regardless of age, to have a timely diagnosis. There’s a concept that EoE is a rare disease, and while that was true in the past, that’s not the case anymore. There are new prevalence data that show 1 in 700 people now have EoE. This means there are about a half-million patients with known EoE, and other data suggest there may be up to twice that many with undiagnosed EoE. So, the message for people in practice is: You’re going to be seeing EoE a lot. You’ll see it in patients coming in with food impactions and getting endoscopies for dysphagia. But, in addition, it’s going to be a percentage of 5% to 7% of patients coming in for upper endoscopy for any condition, especially kids with nonspecific symptoms. So having it on the radar is important. We know that things like concomitant atopic conditions and family history of EoE will increase the chances that the patient with those symptoms will be diagnosed. If we can diagnose EoE without a long delay of symptoms, we’re going to see it in less severe and less strictured phenotypes.

GEN: Do you have any takeaway messages about the guideline?

Dr. Dellon: There are several takeaways from the guideline. Number one is emphasizing the diagnostic process: doing a careful history including asking about eating behaviors, doing a careful endoscopic exam and assessing the endoscopic features (EREFS). Then, developing a rational treatment approach. In the guideline, we have a nice figure on endoscopic findings and how to grade EREFS. We worked hard on the treatment algorithm, and that’s a very nice resource to use. There’s also good information in the supplement. There are cases showing how to implement diet elimination and food reintroduction in practice, and there’s an approach to esophageal dilation as well. It’s a long paper, but if you delve into it, hopefully it’ll be worth your time.

This article is from the May 2025 print issue.