A preprocedure checklist written collaboratively by charge nurses from Mayo Clinic’s gastrointestinal endoscopy and medical care units significantly reduced the number of canceled and rescheduled procedures and enhanced staff communication and satisfaction during a pilot study.

The Mayo Clinic team compared procedure cancellations and other factors before and after implementation of the checklist in a study published in Gastroenterology Nursing (2019;42[1]:79-83). They found that of 25 endoscopy procedures scheduled during the pre-pilot period, six were rescheduled and five were canceled, leaving only 14 procedures completed. In the comparative post-pilot period, 42 of 51 scheduled procedures were performed, with 10 not completed (eight rescheduled, two canceled). Nineteen more procedures were added to the schedule and completed during the pilot period, for a 21% total increase in endoscopy procedure completions.

Of the 14 charge nurses who completed a survey after the pilot study, 79% agreed that the checklist helped reduce procedural delays, 71% agreed that it improved communication and 57% agreed that it contributed to safe patient care.

“Initially, this project stemmed from staff voicing ideas for quality improvement and keeping the patient flow consistent throughout the day. We had many applications that weren’t interfaced between the procedural area and the inpatient units, so we were struggling with patients being appropriately prepped for GI procedures,” explained Susan Wittren, MSN, RN, the nursing supervisor at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “Patients would come down to the procedural area having eaten breakfast, or with a heparin drip still going.”

During the pilot process, the charge nurse in the GI endoscopy unit would initiate a morning report telephone call to the charge nurse in the inpatient unit, during which the RNs would verify that patients met the essential requirements for their upcoming procedures. Items on the checklist included critical laboratory values, nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status and anticoagulation therapies ordered by physicians. “The weekly pilot summary reports incorporated statements of positive reinforcement, which were given when the units achieved stated outcomes,” Wittren and her co-authors wrote.

Since the original pilot study, the checklist has been fine-tuned to be even more GI specific, and has been expanded from the original single inpatient unit for use hospital-wide. “It originally took about 10 minutes to go through the checklists, but with experience, it has become a fairly quick process and only takes a couple of minutes per unit first thing in the morning,” Wittren said.

Working with administrative staff at St. David’s Medical Center, in Austin, Texas, clinicians at Austin Gastroenterology have implemented a similar checklist system based on the SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) approach for facilitating communication, and found it advantageous, said gastroenterologist Harish Gagneja, MD, of Austin Gastroenterology. “While we have not published anything, we do know that our cancellation rate for procedures has gone down, and we have excellent communication with nurses from different parts of the hospital.”

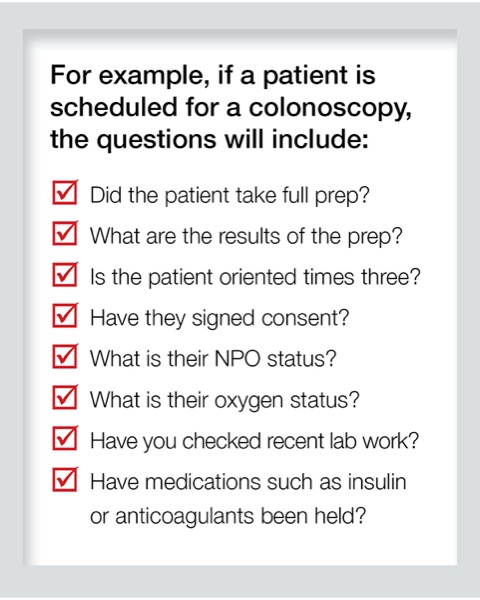

If, for example, a patient is scheduled for a colonoscopy, the questions will include whether or not the patient took full prep, the results of the prep, whether the patient is oriented times three, and whether they have signed consent. It also includes NPO status, oxygen status, recent lab results, and whether medications such as anticoagulants or insulin have been held. “If a patient is in isolation, we will also discuss related arrangements, such as terminally cleaning the room after their procedure or scheduling that patient as the last case of the day,” Gagneja told Priority Report.

The checklist process typically is done between 6 and 7 a.m., allowing enough time to change the sequence of procedures, if necessary, to prevent cancellations. “If the patient’s prep was not done right, or is unclear, then we can intervene to complete the prep in the morning and do the procedure four hours later, rather than having to reschedule for another day,” Gagneja said.

At ProHealth Care Associates, in New York, booking sheets are incorporated into the electronic health record, and the checklists begin with a nursing call to the patient two days before a scheduled procedure. “For colonoscopy preps, a lot of patients think they know what to do but don’t realize when they need to start—kind of like kids leaving their homework until Sunday night,” said Matthew McKinley, MD, the co-chief of the Division of Gastroenterology at ProHealth Care Associates’ facility in Lake Success. “The nurse ensures that the patient has started their two-day prep, or if they are ready to start their one-day prep tomorrow. Do they have the prescriptions? Do they have their instructions?”

Going over such a checklist with patients ahead of time also improves the quality of prep and decreases cancellation rates, McKinley said. “We noticed a tremendous improvement in completed preps once we instituted this process, and if we ever notice problems with scheduling, no-shows and cancellations, it’s almost always because we’re a little short-staffed and those two-day calls weren’t carried out.”

—Gina Shaw

This article is from the December 2020 Priority Report print issue.