SAN DIEGO—Endoscopic band ligation was correlated with a statistically lower amount of rebleeding after diverticular lesion removal than endoscopic clipping in a systematic review and meta-analysis presented at DDW 2025.

“Most people are familiar with … symptomatic abdominal pain of diverticulitis, but it’s [also] a common source of lower GI bleeding” that can put patients at risk for rehospitalization due to anemia, which requires a blood transfusion, James Farrell, MD, a professor of medicine and surgery and the director of the Yale Center for Pancreatic Disease, in New Haven, Conn., told Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News. "From time to time, there is a real need to have a treatment for managing bleeding or treating it initially to prevent rebleeding,” Dr. Farrell said.

In the United States, the most common technique to close diverticular lesions is using clips, but “if you don’t place [clips] correctly, the bleeding will repeat,” noted investigator Alan G. Ortega-Macias, MD, a first-year internal medicine intern at the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque, who conducted the systematic review. Up to 31% of clips result in rebleeding in the first month after the procedure (Intern Med 2018;58[5]:633-638), but, even so, there remains a high preference for clips over EBL, Dr. Ortega-Macias said.

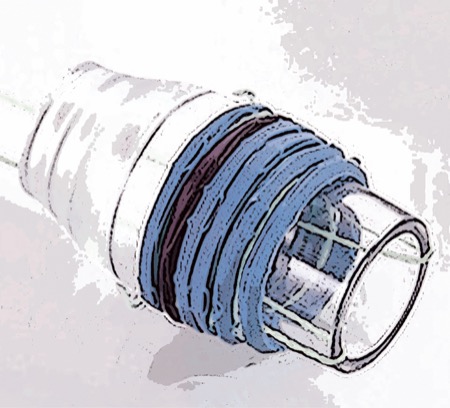

The limited use of EBL for a diverticular bleed likely comes from a lack of clinical trials and sound data to shift away from EC, Dr. Ortega-Macias said. However, EBL is the more common treatment in countries such as Japan, where instead of clipping closed a single diverticular sore, endoscopists cap the larger area around the sore, including the artery, with a balloon to control the bleeding.

The case for EBL, he said, is that it can significantly reduce the chances of rebleeding. One low-risk caveat is that there is a 4% chance that the surrounding tissue within the balloon becomes swollen and inflamed due to more mass within a band versus a clip.

Dr. Ortega-Macias’ systematic review amalgamated five observational studies comparing EBL and EC with respect to early rebleeding rates and an additional four observational studies on late rebleeding rates. Early rebleeding was defined as occurring within 30 days of a procedure, and late rebleeding was classified as occurring after that threshold. Each of the two observational studies included over 2,000 patients, and all studies were conducted in Japan between 2011 and 2022.

The investigators found that early rebleeding rates were lower in the EBL group than the EC group (relative risk [RR], 0.48; 95% CI, 0.35-0.68; P<0.01), and late rebleeding also was statistically lower with EBL than EC (RR, 0.53; 95% CI, 0.30-0.94; P<0.04).

“The next step is a clinical trial,” Dr. Ortega-Macias said. “One limitation is that all the studies included are retrospective and observational. A clinical trial would be a stronger trial in terms of quality to justify banding instead of clipping.”

Dr. Farrell said this research—an updated, larger assessment of existing EBL versus EC literature—has a clear place in helping endoscopists determine the best path forward to treat this subset of patients.

“It needs to be stated that this is a really challenging situation. … These are hard studies to do randomized controls on.” What clinicians can take from this study “is that EBL compared to clipping significantly decreases early and long-term bleeding,” he said.

The main goal, Dr. Farrell noted, is to avoid rebleeding and surgical or radiological intervention. “A significant majority [of patients] will stop rebleeding on their own, but you need to try to identify the culprit lesion and treat it. Any study in that area is valuable.”

—Karen Fischer

Drs. Farrell and Ortega-Macias reported no relevant financial disclosures.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}