Chief of the Digestive Disease Institute

Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, Ohio

This month in the Regueiro Report, I focus on different endoscopic techniques that gastroenterologists might use, one for colorectal cancer detection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease and another to guide treat-to-target decision-making when assessing disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease.

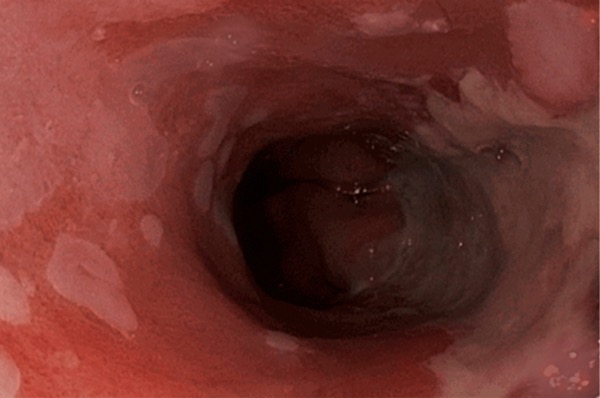

Over the past decade, the approach to detecting early signs of colorectal cancer and dysplasia in certain people with IBD has been dye-based chromoendoscopy. During this process, a blue dye is sprayed during a colonoscopy to visualize flat lesions of dysplasia that are otherwise not visible with a standard colonoscopy. These dysplastic lesions are precursors of colorectal cancer, and not detecting them early could result in missing the opportunity for early treatment and cancer prevention.

Although spray dye chromoendoscopy is an effective approach, it has some limitations. It requires some learning, adds time to the procedure, requires a spray catheter and the appropriate dye, and can be messy. Sometimes the dye can get on the providers or patient, which, while not harmful, may necessitate cleaning. Finally, most colonoscopes today are high-definition and have an ability to replicate chromoendoscopy without using dye, for example, by using narrow band imaging with the push of a button on the scope.

The first study in this month’s report found that high-definition white-light endoscopy is as effective at detecting early signs of cancer as dye-based chromoendoscopy. Importantly, the colonoscopes used in this study were high-definition scopes, and investigators performed a careful inspection of the colon lining by withdrawing the colonoscope from the cecum per 10 minutes withdrawal time. We know that more accurate detection of colon lesions occurs when our withdrawal time is longer.

When dye-based chromoendoscopy was introduced several years ago, many colonoscopes were not high-definition. Now, almost all our colonoscopes are high-definition scopes, and it is possible that this is why white-light high-definition endoscopy was just as effective as spray dye chromoendoscopy at cancer detection.

{RELATED-VERTICAL}This study’s finding dovetails with my own practice of using high-definition white-light endoscopy as a powerful tool for detecting lesions we may have missed in the past with standard-definition scopes. However, there are still times when it may be appropriate to use spray dye chromoendoscopy, such as in people with primary sclerosing cholangitis who are at risk of developing flat, more difficult-to-see lesions (especially in the right side of the colon) that have a higher likelihood of becoming cancerous.

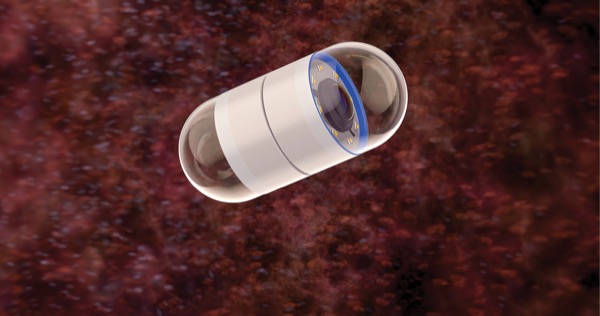

The second study evaluates the use of video capsule endoscopy (VCE) in the management of quiescent Crohn’s disease. All study participants had evidence of mucosally active CD but were in steroid-free remission without symptoms. After the baseline VCE, some participants received serial VCEs in a treat-to-target approach, with the target being mucosal healing of CD. This treat-to-target group had VCE every six months with changes and/or optimization of their therapies.

Other participants did not undergo every-six-month VCE but were in a standard care arm. Accordingly, a change in treatment or escalation of treatment was at the discretion of the physician based on the patients’ symptoms. The authors found that the serial VCE group, which received treat-to- target care, had fewer clinical flares and more mucosal healing at 24 months.

This is an exciting study that shows that VCE can guide improvements in clinical outcomes and underscores the importance of treat-to-target management of IBD. That said, I do not routinely use VCE for everyone with asymptomatic CD. A potential but rare complication from this approach is a retained capsule in the small intestine that requires endoscopic or surgical retrieval. Today we typically perform a dissolvable patency capsule first to make sure the video capsule won’t get stuck. However, this does add additional visits, an X-ray, and sometimes lack of payor coverage for the patency capsule investigation.

Generally, I monitor the small bowel in certain patients with CD using biomarkers, such as fecal calprotectin and C-reactive protein, as well as imaging, such as intestinal ultrasound or cross-sectional scans (CT scan or MRI). Nevertheless, this study adds suppport for the growing number of imaging tools for treat-to-target care of CD.

White light endoscopy versus dye-based chromoendoscopy

Gut 2025;74(4):547-556

A total of 563 adults with IBD and no active disease who were scheduled for endoscopic surveillance were randomized 2:2:1 to high-definition white-light endoscopy with re-inspection of each colonic segment; high-definition chromoendoscopy; or single-pass high-definition white-light endoscopy without colonic inspection. Colorectal lesion detection rates were 10.3% (24/234) for white-light endoscopy with colonic re-inspection and 13.1% (28/214) for chromoendoscopy; this was within the study’s noninferiority margin of 10% for white-light endoscopy. In addition, the number of detected colorectal neoplasias per 10 minutes of withdrawal time was similar for white-light endoscopy with reinspection and chromoendoscopy (0.062 vs. 0.058; P=0.83).

Capsule endoscopy-guided treat-to-target vs. standard care in quiescent CD

Gastroenterology 2025:S0016-5085(25)00519-0. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2025.02.031

All participants in this study had quiescent CD, were steroid-free and completed VCE at baseline. These exams revealed Lewis inflammatory scores for each person; scores at or above 350 indicated a high risk for CD relapse.

Twenty participants then received VCE every six months for 24 months, which led to changes in the dosage or type of their biologic therapy or initiation of another biologic. This was the treat-to-target group. The usual-care group included another 20 participants, equally at risk for relapse, who continued usual care without more VCE tests.

At 24 months, there had been five clinical flares (5/20; 25%) in the treat-to-target group, compared with 14 flares (14/20; 70%) in the usual-care group (odds ratio, 0.14; 95% CI, 0.04-0.57; P=0.006).