PHILADELPHIA—Rates of post–endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis remain high, according to the results of a study analyzing data from the National Readmissions Database presented at ACG 2024. Gregory Coté, MD, MS, a professor of medicine and the division head of gastroenterology and hepatology at Oregon Health & Science University, in Portland, suggested some potential drivers of the stubbornly high morbidity, as well as some potential tips for avoiding it.

The retrospective study, led by Saadia Nabi, MD, a resident at HCA Florida Aventura Hospital, identified a cohort of more than 1 million patients from the database who underwent ERCP and compared those who developed post-ERCP pancreatitis (PEP) with those who did not (poster 0035).

Presenting the findings, Dr. Nabi reported that among those who underwent ERCP, 16.6% developed PEP. These patients had a longer length of stay than those who did not develop PEP (7.9 vs. 6.1 days; P<0.001) and were more likely to have been treated in a large hospital (odds ratio [OR], 1.11; P<0.001).

Dr. Coté, who was not involved in the study, said the findings support other studies “that show persistently high or higher rates of PEP in the past decade. So, the observation is real.”

Regarding drivers of this high PEP risk, Dr. Coté offered several potential explanations. “Perhaps we have lower thresholds to admit patients after ERCP than before, which could result in a detection bias,” he explained. If “patients have higher baseline comorbidity,” he said, that could be another potential explanation.

He also noted that the United States has more ERCP providers than ever before. “It is possible that technical expertise has atrophied somewhat as the procedure has moved from a few ‘hallowed halls’ to across the U.S. health system. It’s unreasonable to expect a busy practicing gastroenterologist to cannulate and manipulate the ducts with the same finesse that first- and second-generation ERCP providers developed, as they performed the procedure almost exclusively in their practices,” he said. “Admittedly, this is conjecture, but post-ERCP pancreatitis is more common than ever—morbidity from ERCP is higher than ever—in spite of all that we have learned about this procedure in the past five decades.”

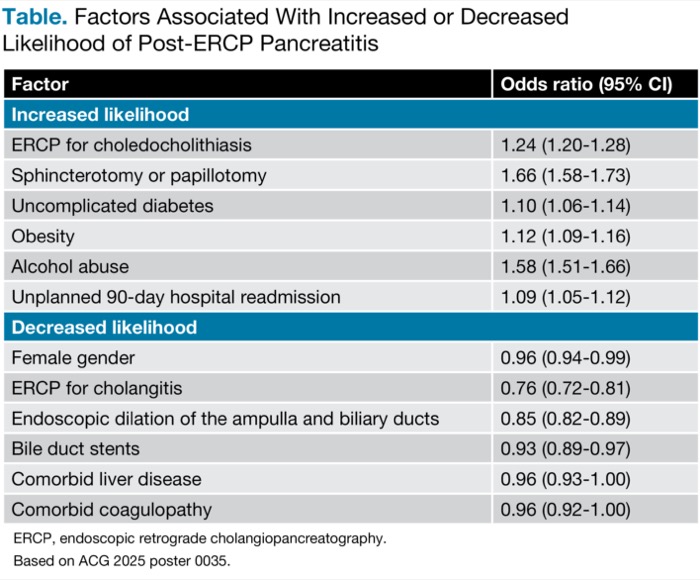

When looking at ERCP indication, Dr. Nabi and her co-investigators found that among procedure details and patient demographics and comorbidities, their multivariable model found several factors were associated with an increased likelihood of PEP. Patients who developed PEP were more likely to have undergone ERCP for choledocholithiasis or have had sphincterotomy or papillotomy (OR, 1.66; 95% CI, 1.58-1.73) than those who did not develop PEP (Table). In addition, patients who developed PEP were more likely to be older and have uncomplicated diabetes, obesity or alcohol abuse than those who did not develop PEP. ERCP patients who developed PEP were also more likely to have unplanned 90-day hospital readmission.

| Table. Factors Associated With Increased or Decreased Likelihood of Post-ERCP Pancreatitis | |

| Factor | Odds ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|

| Increased likelihood | |

| ERCP for choledocholithiasis | 1.24 (1.20-1.28) |

| Sphincterotomy or papillotomy | 1.66 (1.58-1.73) |

| Uncomplicated diabetes | 1.10 (1.06-1.14) |

| Obesity | 1.12 (1.09-1.16) |

| Alcohol abuse | 1.58 (1.51-1.66) |

| Unplanned 90-day hospital readmission | 1.09 (1.05-1.12) |

| Decreased likelihood | |

| Female gender | 0.96 (0.94-0.99) |

| ERCP for cholangitis | 0.76 (0.72-0.81) |

| Endoscopic dilation of the ampulla and biliary ducts | 0.85 (0.82-0.89) |

| Bile duct stents | 0.93 (0.89-0.97) |

| Comorbid liver disease | 0.96 (0.93-1.00) |

| Comorbid coagulopathy | 0.96 (0.92-1.00) |

| ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Based on ACG 2025 poster 0035. | |

Dr. Coté posited two potential explanations for increased odds of PEP among those with choledocholithiasis. “First, choledocholithiasis is more likely to represent a patient with a native papilla, so [they] have a higher likelihood of a difficult biliary cannulation, pancreatic orifice trauma, et cetera,” he said. The second reason could be that “many of these cases coded as choledocholithiasis may have already passed a stone or never had a stone at all. They just demonstrated features consistent with a stone, like a dilated duct or abnormal liver tests.

“Now we are slipping into the old world of sphincter of Oddi dysfunction and papillary stenosis, notorious conditions associated with post-ERCP pancreatitis,” he explained. With this in mind, Dr. Coté said that “in this age of endoscopic ultrasound and magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography, nearly every ERCP performed for choledocholithiasis should have a stone removed.” Indeed, having a stone removed was found to be associated with lower odds in the study (OR, 0.79; 95% CI, 0.76-0.82).

Additional factors that were less common among patients who developed PEP than those who did not included female gender, ERCP for cholangitis, endoscopic dilation of the ampulla and biliary ducts, bile duct stents, comorbid liver disease, and comorbid coagulopathy (Table).

{RELATED-VERTICAL}Dr. Nabi suggested that their findings from “a large, nationally representative cohort” can be used to “inform healthcare policies and interventions aimed at reducing PEP incidence, ultimately improving patient outcomes and enhancing the quality of care.”

Dr. Coté said a key takeaway from this study and others that have shown high incidence of PEP is to “always remember that you cannot cause post-ERCP pancreatitis if you don’t do an ERCP. Be sure the indication is airtight.” He added that “you should have the technical skill to leave a prophylactic pancreatic duct stent in the event that you inadvertently engage the pancreatic duct, something that happens even in the best of hands.”

Smart case selection is one factor that Dr. Coté said likely would lower rates of PEP. He advised “not offering ERCP for suspected choledocholithiasis and only engaging the papilla when we are pretty certain from endoscopic ultrasound or another imaging test that a stone is present and not performing ERCP for abdominal pain alone or with a nonspecific finding like a dilated bile duct or minimal liver test abnormality.” In these cases, he stressed, “the stakes are just too high.”

—Natasha Albaneze, MPH

Drs. Coté and Nabi reported no relevant financial disclosures.