The American College of Gastroenterology recently released an updated clinical guideline on acute pancreatitis. GEN’s Sarah Tilyou spoke with lead author Scott Tenner, MD, MPH, JD, FACG, the director of Brooklyn Gastroenterology and Endoscopy, the director of The Greater New York Endoscopy Center, a clinical professor of medicine at the State University of New York – Health Sciences Center, and an adjunct professor of law at Fordham University School of Law, in New York City, about the updated guideline. Dr. Tenner, who has been doing research on pancreatitis for 35 years, shared insights about the development of the guideline and its implications for GI practice.

GEN: What’s new in the guideline that clinicians need to know?

Dr. Tenner: There are three criteria for establishing a diagnosis of acute pancreatitis: abdominal pain consistent with the disease, serum amylase and/or lipase greater than three times the upper limit of normal, and abnormal findings on imaging, such as CT or MRI. You need two of these three to establish the diagnosis, and that has been the dogma for decades. However, we discuss in the new guideline that there’s a big problem with overdiagnosis because many patients are walking around with amylases and/or lipases that are greater than three times the upper limit of normal. Many patients who come to the ER with gastroenteritis with nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain are found to have lipases or amylases that are greater than three times the upper limit of normal and are incorrectly diagnosed with acute pancreatitis. This can lead clinicians to wonder whether the patient should be admitted because, technically, every patient with acute pancreatitis should be admitted and observed. But the problem is that the diagnosis is just simply wrong. That’s why the patients seem to get better in the ER within 12 hours. So, the new guideline discusses how to take a more nuanced approach to diagnosis.

Another change we discussed was in regard to etiology. Historically, drugs have been blamed as causing acute pancreatitis in about 5% to 10% of patients. The new guideline explains that very few drugs cause acute pancreatitis. With some exceptions, such as azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine, blaming a drug is probably the wrong approach. We’ve also expanded on idiopathic acute pancreatitis, noting that in about one-third of patients, there will be no obvious diagnosis. There won’t be gallstones or alcohol overuse. The diagnosis is just idiopathic. It should be accepted that in one-third of patients, you won’t find the diagnosis, and you don’t have to subject patients to further testing. However, it is important to remember that 2% to 3% of patients over the age of 40 years with pancreatic cancer present initially with acute pancreatitis. So, if you think a patient over 40 has idiopathic pancreatitis, it is important to do some more imaging studies, either magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography or endoscopic ultrasound, within the next few weeks.

GEN: How might the guideline change practice?

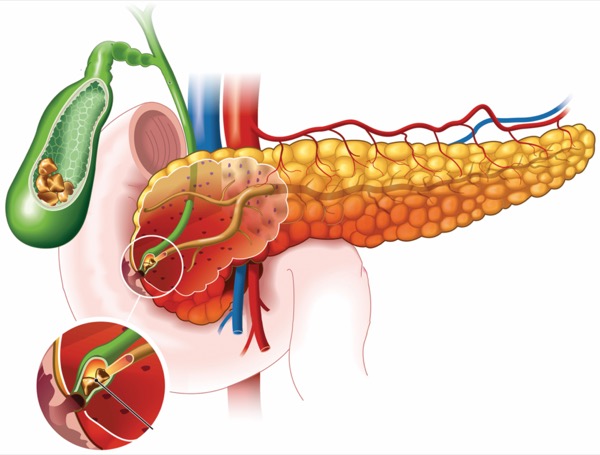

Dr. Tenner: The guideline panel emphasized the importance of preventing post–endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pancreatitis. When I was a fellow, about 10% to 15% of people who had an ERCP would get pancreatitis and about 1% to 2% had severe disease. That’s an enormous number of patients. For an institution doing hundreds of ERCPs per year, you’re talking about three, four or five patients going to the ICU because they had this procedure done, and 1 in 10 being admitted for a complication from the procedure.

But now, the risk of getting post-ERCP pancreatitis is very low—for severe acute pancreatitis, probably 1 in 1,000—because we’ve come up with some important interventions. Aside from making sure the patient really needs to undergo the procedure, the guideline focused on three interventions supported by data generated over the last decade. The first is judicious use of rectal indomethacin. Using 250 mg of indomethacin suppositories around the time of the procedure significantly decreases the risk for pancreatitis and severe post-ERCP pancreatitis in patients undergoing specific interventions such as an ampullectomy or a pancreatic sphincterotomy. Second, right before the guideline came out, a multicenter trial showed that in some patients, pancreatic duct stents are needed with the rectal indomethacin suppositories (Lancet 2024;403[10425]:450-458). Lastly, over the last decade, it has become clear that if you give patients a liter or two of IV fluids, such as lactated Ringer’s, before ERCP, it seems to prevent severe post-ERCP pancreatitis. We believe, based on animal studies looking at the microangiopathic effects of fluids and the disease, that the fluids are keeping the blood vessels open and pancreas hydrated. The way it prevents severe disease is preventing necrosis of the pancreas. This is now incorporated into the guideline for preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis.

GEN: What were some of the hottest points of debate on the guideline panel, and how did you resolve them?

Dr. Tenner: The pancreatologist authors didn’t disagree on much, other than some minor differences about how to phrase a few things. But we did have some disagreements with the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) methodologists who were involved in the guideline this time. There are very few randomized prospective controlled clinical trials in acute pancreatitis, and this limits our ability to say that we have excellent quality evidence for the guideline statements. As pancreatologists, we rely on the evidence from basic science, from animal studies, from retrospective studies, but the GRADE authors felt very strongly that we had to tone our guidance language down, using “we suggest,” not “we recommend.” It was difficult for me and the other pancreatologists on the panel because we feel strongly, but the GRADE methodologists pushed back, saying the guideline could only present information as a suggestion or as a key concept, not as a recommendation.

I can tell you as an attorney, it’ll be harder for a plaintiff’s attorney to say that a healthcare practitioner violated the standard of care if that suggested approach is not employed, because it is only a suggestion. For a defense attorney, it’ll be harder to say a clinician relied on the guideline, again because there are only suggestions, and this can raise the question, “Why didn’t you do something else?”

A specific area that has come under debate is use of aggressive IV hydration. It had been the dogma that aggressive IV hydration early in the course of acute pancreatitis prevents complications. The ACG, American Gastroenterological Association and other organizations all recommended this. Then, in 2022, a randomized trial called the WATERFALL study showed that if you give high doses of fluids to all patients, you’re more likely to have complications from volume overload rather than showing any benefit (N Engl J Med 2022;387[11]:989-1000).

This is just one study, but it rocked the whole field of pancreatology because this went against everything that we had thought. So, in the current guideline, we don’t recommend early, aggressive IV hydration anymore. We tone it down and suggest using moderately aggressive hydration early on.

But the problem in the management of acute pancreatitis, in general, is that the first six to 12 hours are the key with IV hydration. Clinicians are busy, and after we admit the patients from the ER, we may not get back to see them for 12 hours. During those 12 hours, a patient with acute pancreatitis who looks perfectly fine with a bellyache in the ER, 12 hours later is not putting out urine, they’re tachycardic, they’re hypotensive, all because not enough fluids were given in the transfer, and you missed that important window for when to give the IV hydration. I think the reason the WATERFALL study showed you can use lower rates of hydration in patients with acute pancreatitis who are not hypovolemic is that the investigators were watching their patients closely. The clinicians checked them starting at three hours.

So, in our guideline, we explain that, yes, you can back off early, aggressive IV hydration and call it early, moderately aggressive hydration. But if you do that, you have to check the patient three hours later, six hours later, etc., like they did in the study, and give fluids as needed. If you look at the appendix in the study, the clinicians were giving much more fluid, as the patients needed it.

I think a study that needs to be designed would evaluate moderate hydration with close monitoring. That study cannot be done by gastroenterologists alone, because very often when a patient with acute pancreatitis goes to the ER, they may not look bad. But by the time they are seen by gastroenterology, they have worsened. The guideline underscores that one of the risk factors for severe disease is how long the patient was managed before they saw a gastroenterologist. The key to the fluids is the first 12 to 24 hours, so the study would have to be performed with gastroenterologists working with surgeons and ER physicians who may be managing patients during that early period.

GEN: What are some of the biggest remaining gaps in this area?

Dr. Tenner: There are two things we would love to do. The first is identify which patients are at risk for severe disease. With acute pancreatitis, 75% to 80% of the patients are going to have a terrible bellyache for three to five days, but then they’ll go home and be fine, and we can do whatever intervention is needed to prevent recurrent attacks. But we would like to find out some way of identifying patients in that group who are going to be the other 20% or 25% who develop multisystem organ failure and necrosis.

When I was a fellow, there were a few studies showing that we could identify in the ER which patients were going to develop severe disease using urinary trypsinogen activation peptide (TAP). We were so excited we were going to have the first urinary test to determine which patients were going to get severe disease. But the company that attempted to develop it was unable to figure out how to reproduce the antibody test, and since that time, no one’s done any research in that area.

I still believe that if you can get TAP or some test that you can use in the ER to identify those at higher risk, we would know which patients should get aggressive hydration, which patients could benefit from ICU monitoring early on. That would really help us, rather than having all the patients go to the floor and then sometimes we miss the ball and find out too late that the patient needed more aggressive hydration.

This leads me to the second area where gaps remain: treatment of acute pancreatitis. This is a disease that affects 300,000 people per year in the United States. The market is huge, and the disease is so painful and has such an unpredictable course that anything that would decrease the complications by even 5% or 10% would become the standard of care. There are so many biologics out there targeting different parts of the inflammatory cascade of multiple diseases. I could give reasons, from a basic science standpoint, why many of them would work in acute pancreatitis. But very few of them have ever been tried in humans or animals, let alone in randomized trials in which we can get enough patients included to see whether we can make a difference. But I would like to hope that the pharmaceutical companies will want to invest in more randomized trials. One thing’s for sure: The pancreatitis community is very motivated and committed to get involved in research and make the breakthrough in this disease.

{RELATED-VERTICAL}On a positive note, in the last 30 years, the mortality from acute pancreatitis has decreased 50% to 60%. It used to be 5% or 6%, and we’re down to 2% to 3% because of a lot of these interventions, whether it be preventing post-ERCP pancreatitis or treating the pancreatitis with better IV hydration early on and monitoring patients. But there’s still a ways to go—1 in 30 to 1 in 50 people with acute pancreatitis still die from the disease.

GEN: What are the key takeaways from the guideline?

Dr. Tenner: The most important aspect in managing a patient with acute pancreatitis, certainly in the first 12 to 24 hours, is monitoring them closely and watching for tachycardia, because by the time they get hypotensive, it’s too late. Laboratory tests are very important, such as watching the blood urea nitrogen, the hematocrit, making sure patients don’t get dehydrated. It’s also very important to keep in mind what risk factors patients carry with them that pose a risk of developing severe disease, such as obesity, comorbidities and older age. These patients probably should be in a monitored setting. And if you see systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) develop in a patient—if they have leukocytosis and tachycardia, they have SIRS—this is a predictor of organ failure in patients with acute pancreatitis. So, the most important thing a clinician can do for a patient with acute pancreatitis is to closely monitor them the first 12 to 24 hours and do not miss the goal with therapy, as discussed in the guideline.