Knowing how to “approach difficult or incomplete colonoscopy … is one of the most important things that gastroenterologists should all learn,” according to Jonathan Leighton, MD.

Both patient and technical factors can lead to an incomplete colonoscopy, with anatomic difficulties commonly posing challenges, said Dr. Leighton, a professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology at Mayo Clinic in Arizona, and the current president of the American College of Gastroenterology.

Angles and Narrowing and Loops, Oh My!

“When you think about why we have trouble with one of the anatomic variations, it’s usually either an angulated or narrowed sigmoid colon or redundant colon,” he explained. Navigating these scenarios requires proactive colonoscopists who can quickly identify the altered anatomy and use techniques such as “torque steering, right-left controls and … in really difficult situations, the two-hand technique,” said Dr. Leighton, presenting his tips and an overview of technologies to minimize incomplete colonoscopy at NYSGE 2023.

For angulated or narrow sigmoid colons, which are more common in young or slender women and those with previous pelvic surgery, Dr. Leighton recommended the use of smaller diameter scopes, scopes with a shorter bending section and water immersion, emphasizing the need for “patience” and “exquisite control of the shaft and tip deflection.” He also stressed the importance of straightening the scope and reducing loops as much as possible after passing the angled or narrowed section.

Redundant colon is most common at the hepatic flexure and in tall men and people with obesity. To Dr. Leighton, recognizing loops is one of the key initial steps in approaching a difficult, redundant colon. “I always emphasize to my fellows the importance of identifying loop formation” by a lack of a 1:1 transmission of force to the tip of the colonoscope “and too much scope in the patient.”

Dr. Leighton noted that loop reduction can be accomplished using adult standard scopes, water immersion and overtubes but also mentioned additional considerations and strategies. For example, he said using “variable stiffness can increase cecal intubation rates and cecal intubation time” and using positional changes—changing to the supine position to cross the transverse colon—could aid in loop reduction. In some instances, however, Dr. Leighton said colonoscopists have to carefully and gently push through a loop, provided the patient tolerates it.

Building on Dr. Leighton’s advice, Shai Friedland, MD, MS, a gastroenterologist and professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, in California, told Gastroenterology & Endoscopy News that “newer balloon-tipped overtubes designed for colonoscopes can be especially helpful in loopy colons.” He pointed out that “one of the neat benefits is that if you still can’t reach the cecum, you can leave the overtube in the colon and exchange the colonoscope to a longer enteroscope without having to come out.”

Beyond the specific examples of tortuous sigmoid and looping colons, “in all types of difficult colons,” Dr. Friedland said, “excessive gas instillation during colonoscopy is a real enemy [because] it can make progress difficult or impossible.” He noted that using a “water immersion or water exchange technique is a great way to avoid this.”

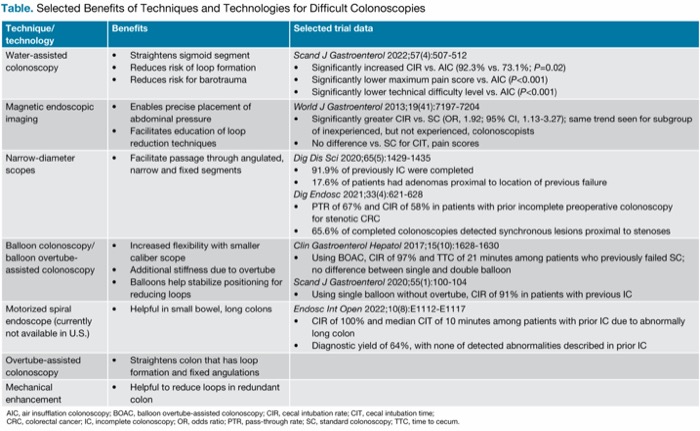

If these strategies are not successful, Dr. Leighton outlined several more techniques and technologies that that can be employed (Table).

| Table. Selected Benefits of Techniques and Technologies for Difficult Colonoscopies | ||

| Technique/ technology | Benefits | Selected trial data |

|---|---|---|

| Water-assisted colonoscopy |

| Scand J Gastroenterol 2022;57(4):507-512

|

| Magnetic endoscopic imaging |

| World J Gastroenterol 2013;19(41):7197-7204

|

| Narrow-diameter scopes |

| Dig Dis Sci 2020;65(5):1429-1435

|

| Balloon colonoscopy/ balloon overtube- assisted colonoscopy |

| Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017;15(10):1628-1630

|

| Motorized spiral endoscope (currently not available in U.S.) |

| Endosc Int Open 2022;10(8):E1112-E1117

|

| Overtube-assisted colonoscopy |

| |

| Mechanical enhancement |

| |

| AIC, air insufflation colonoscopy; BOAC, balloon overtube-assisted colonoscopy; CIR, cecal intubation rate; CIT, cecal intubation time; CRC, colorectal cancer; IC, incomplete colonoscopy; OR, odds ratio; PTR, pass-through rate; SC, standard colonoscopy; TTC, time to cecum. | ||

Approaching Subsequent Colonoscopies

In patients who do end up with an incomplete colonoscopy, Dr. Leighton emphasized the benefits of having an expert endoscopist do the repeat procedure, as opposed to doing radiographic imaging, and doing so in a timely manner when possible. Radiographic imaging can be less sensitive for detecting polyps than malignant obstruction, “so repeat colonoscopy by an expert always should be the first choice,” he noted, citing a recent retrospective study (Gastrointest Endosc 2020;91[6]:1371-1377).

In addition, pointing to results from a Canadian population-based study (Dig Dis Sci 2013;58[8]:2151-2155), Dr. Leighton said “patients instructed to have next-day follow-up were significantly more likely to adhere to the recommendation [to repeat colonoscopy] compared to those who were instructed to return after longer intervals.”

Dr. Friedland added that adjusting the sedation strategy after an unsuccessful colonoscopy also can be beneficial. “Adequate sedation is very helpful in patients with difficult colons. So, if the colonoscopy was unsuccessful with nurse-administered moderate sedation, it might help to reschedule with deep sedation administered by an anesthesiologist.”

Mike Wei, MD, a gastroenterologist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine, suggested that “if needed,” gastroenterologists also “could always refer to a tertiary center to endoscopists with a specialization for managing incomplete colonoscopies.”

Be Flexible and Judicious

In summarizing his tips for approaching difficult colonoscopies, Dr. Leighton said, first, “it’s really important to classify the anatomic problem and learn how to deal with that,” including not hesitating to change instruments and solutions when navigating altered sigmoid anatomy or looping. He stressed that colonoscopists should “try something once or twice, but if it’s not working, realize there are other options.” Ultimately, it’s also critical “to be willing to quit, because there are other ways you can look at the colon when it comes down to it.”

Dr. Friedland echoed this sentiment, noting that “there are very rare patients with extremely fixed left colons—for example, due to multiple episodes of diverticulitis—and it’s important to know when to stop, because avoiding a perforation on a screening colonoscopy is more important than having a 100% cecal intubation rate.”

—Natasha Albaneze, MPH

Drs. Friedland and Leighton reported no relevant financial disclosures. Dr. Wei reported financial relationships with Capsovision and Neptune Medical.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}