The American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) and American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) recently released an updated clinical guideline on the pharmacologic management of chronic idiopathic constipation (Gastroenterology 2023;164[7]:1086-1106). GEN’s Sarah Tilyou spoke with lead author Lin Chang, MD, AGAF, FACG, the vice chief of the Vatche and Tamar Manoukian Division of Digestive Diseases and director of the GI fellowship program at the University of California, Los Angeles, about the impetus for the guideline and what it means to GI practice.

GEN: What prompted the guideline?

Dr. Chang: There hasn’t been a guideline on chronic idiopathic constipation (CIC) for quite some time. The AGA and the ACG, at a very similar time, wanted to develop guidelines for CIC treatment. So, members from both societies worked together on this guideline—the first joint guideline of these two leading GI societies.

We thought the joint approach would be stronger, more efficient and result in consistency in the recommendations. If there are different guidelines, and one recommends a treatment and another doesn’t, there might be some confusion among providers, patients and payors. Developing a joint guideline and issuing a strong recommendation shows we have all agreed, at least in the United States, that a treatment should be recommended. I think that’s really important.

We took the strengths of both societies and the way each creates guidelines and did it together. We hope this will be a road map for future joint guidelines between the two societies.

GEN: What’s new in the guideline that clinicians need to know?

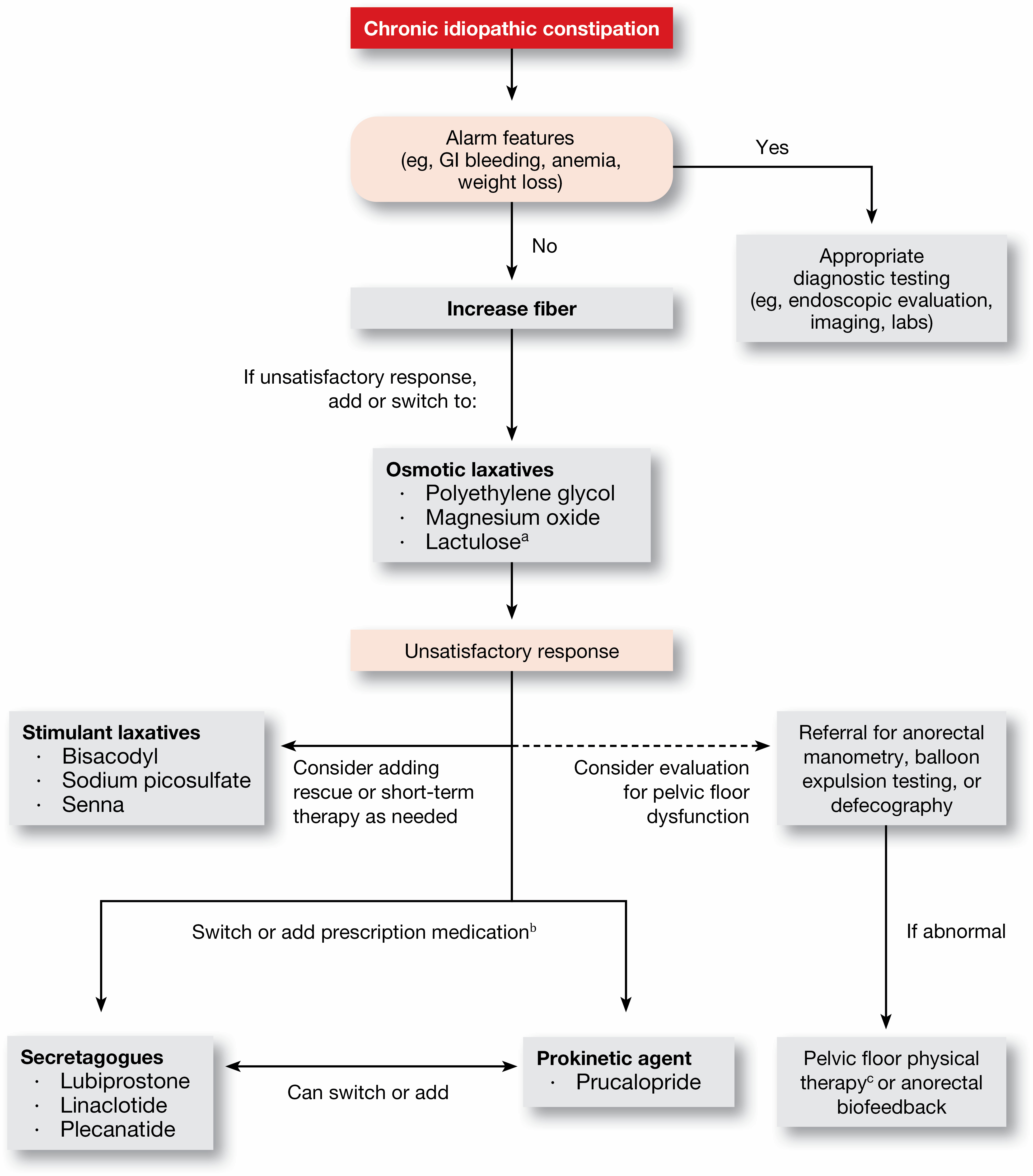

Dr. Chang: There are some new treatments that have not been evaluated or assessed in a guideline because the last one was many years ago and it did not use GRADE [Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation] methodology. We have over-the-counter remedies, including magnesium and stimulant laxatives, such as senna-based laxatives, that have never really been included in guidelines. We also looked at fiber. Then, we looked at pharmacologic agents, some of which are newer, such as linaclotide (Linzess, AbbVie/Ironwood), plecanatide (Trulance, Salix), and prucalopride (Motegrity, Takeda). In addition, the panel developed a treatment algorithm as an accessory piece to help clinicians in their practice (Figure).

In general, none of the treatments were recommended with a high certainty of evidence, but some of them did get a strong recommendation. A strong recommendation means that you would recommend it in most of the patients, but there’s a small group of patients for whom you wouldn’t recommend it. A conditional recommendation means that you would recommend it in the majority of individuals, but there’s going to be a substantial number that you’ll determine by their individual characteristics whether this is the right treatment based on the risk and benefit. In that case, you really have to consider multiple factors before you would actually recommend that treatment.

GEN: How might the new guideline change practice?

Dr. Chang: I think it’s helpful for clinicians and patients to have the scientific evidence when they’re deciding whether or not to use a treatment. However, because some of the recommendations are not exclusively supported by scientific evidence, each of our guideline statements comes with implementation remarks to help explain how the recommendations can be applied in clinical practice.

Several treatments were given strong recommendations: the osmotic laxative polyethylene glycol, and the stimulant laxatives bisacodyl/sodium picosulfate, linaclotide, plecanatide and prucalopride. The level of evidence on which these recommendations were based was moderate.

The guideline also includes conditional recommendations for fiber, magnesium oxide, lactulose, senna and lubiprostone, with levels of evidence supporting them varying from very low to low.

But there was further discussion about when and how the treatments could be used in practice. For example, we recommended using polyethylene glycol, but the implementation remark discusses how a trial of fiber supplementation can be considered for mild constipation before polyethylene glycol, or the two options could be combined. Also you can try OTC agents first-line, but if someone has more severe symptoms, you can start with polyethylene glycol in conjunction with OTC treatments. This type of nuance needs to be applied if someone’s coming in with more severe constipation.

Another example is lactulose. Although there are some data on lactulose, it is not high-quality evidence, and in clinical practice, it’s very well known that lactulose is associated with gas and bloating, which are symptoms that patients with constipation already have. So, even though it could be considered a potential first-line therapy, in general, you probably wouldn’t use it first-line because of the side effects and you would consider it later down the line.

GEN: What were some of the hottest points of debate, and how did you resolve them?

Dr. Chang: Looking at the evidence and making guidelines statements, there was not really anything that generated a lot of conflict. However, one important area that was a little bit more debated was defecatory disorders. Patients with chronic constipation can have slow-transit or normal-transit constipation, but some of them also have a defecatory disorder such as dyssynergic defecation, or pelvic floor dysfunction. We didn’t look at this evidence because it was already reviewed fairly recently (Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116[10]: 1987-2008), but we incorporated it in our treatment algorithm.

There was some discussion and difference of opinion about when you would assess for a defecatory disorder, and the reason that’s important is because the treatment is different. If this is present, treatment should not consist only of laxatives or other constipation medications. They may need biofeedback or pelvic floor physical therapy because that works better in that setting. Some patients may need both. We agreed that in patients who failed OTC remedies, you really should investigate for pelvic floor dysfunction or dyssynergic defecation. If you haven’t assessed it and the patient already is on prescription treatments and is not responding as well as you had expected, then you should definitely think about a defecatory disorder predominantly contributing to their symptoms.

GEN: Where are the biggest remaining gaps in evidence?

Dr. Chang: The [studies of] older OTC remedies haven’t been high-quality clinical trials, and I’m not sure anybody’s going to do that at this time. These older studies did not use FDA-recommended end points for CIC. Some of them were shorter, for example two or four weeks. If you’re doing a trial for a very short period of time, is that really giving you an idea of how a patient would do if they took the treatment for a longer period of time, as they would need to for chronic constipation? It would be nice to have longer-term studies using accepted patient-reported outcome measures. That may not be done for older treatments, but it’s done for the newer treatments.

Other areas that need more study are dietary recommendations, other than adding fiber, and behavioral treatments for chronic constipation.

GEN: What is the most important take-home message for clinicians about the guideline?

Dr. Chang: I would use this evidence and the guidelines to guide clinicians and patients on what’s the level of evidence, even though a lot of it may not be good. You have to use a number of other individual factors, such as patient preference, prior treatments, primary symptoms and patient expectations. Then, you can determine what’s the best personalized treatment for them. This is not meant to be a “live and die by” guideline. It’s really more to assess the scientific evidence and encourage clinicians to incorporate clinical experience and practice into decision making, so they can do what’s best for each patient.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}