University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington

Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine

Roanoke

Endoscopic detection and resection of colorectal polyps is the key determinant of the eventual prevention of colorectal cancer. Whereas visualization of sessile and pedunculated colon polyps is relatively straightforward and easy, finding flat or sessile serrated lesions is more challenging.

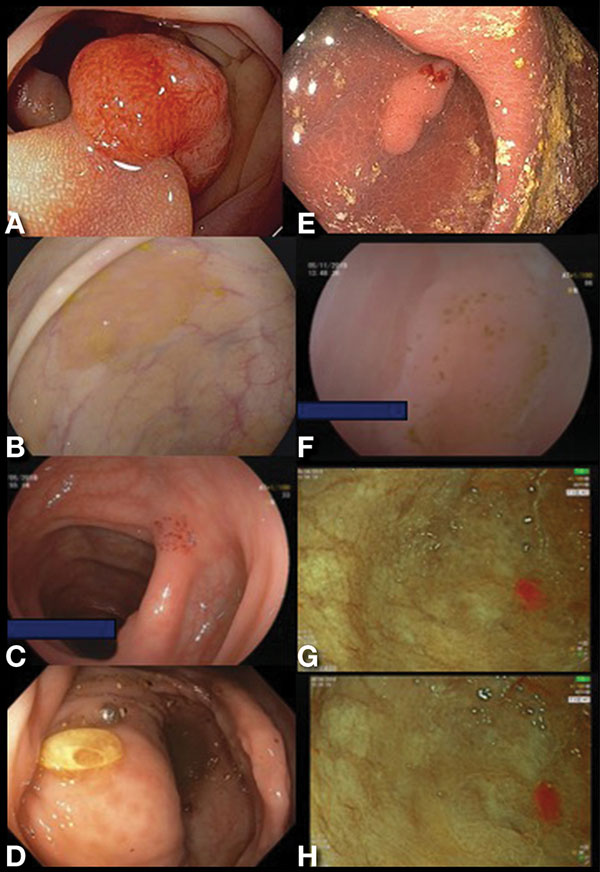

These flat and sessile serrated lesions tend to secrete mucus or accumulate debris or stool on their surface, which changes the appearance of these lesions, hindering the ability of visual aid systems using artificial intelligence, or traditional virtual or dye-based chromoendoscopy techniques, to recognize them (Figure 1).

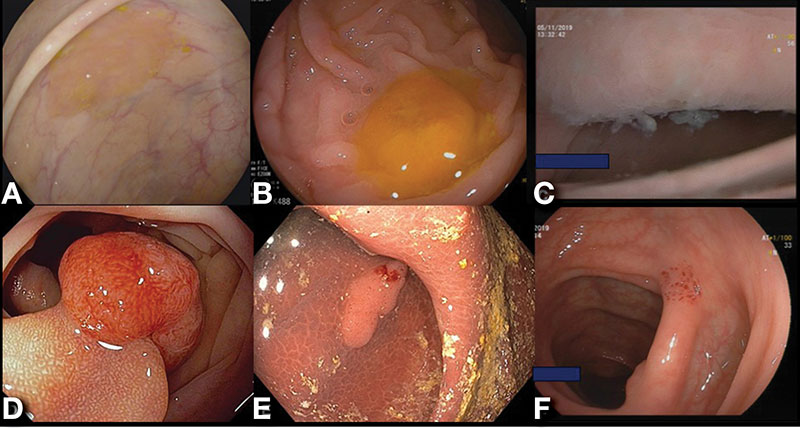

We have called the spontaneous or natural way of changing or adding color to the surface “biologic or natural chromoendoscopy.” In serrated lesions, 2 consistent and unequivocal changes that affect goblet cell mucin secretion, and thus appearance of these lessions, is loss of O-acetyl substituents at sialic acid C4 and increased sialylation at C7,8,9. Other biologic chromoendoscopy presentations that change the appearance of lesions are “chicken skin mucosa” and melanosis coli (Figure 2).

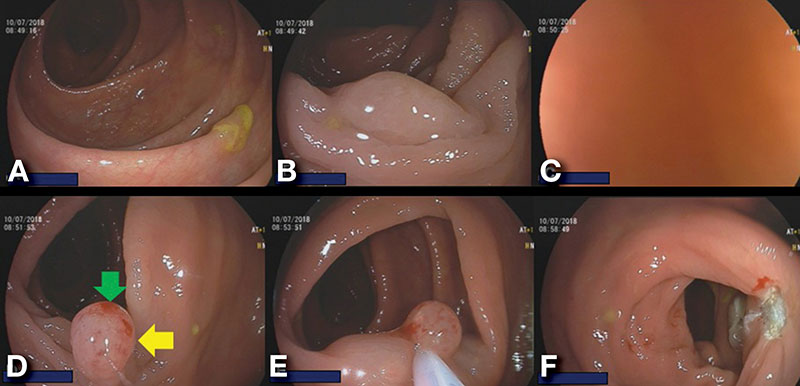

Chicken skin mucosa is present in sessile and/or neoplastic lesions, and melanosis coli improves the detection of any colorectal polyp. We also have developed a technique to mark the polyp using a suction mark and reshape it by suctioning the polyp into the suction channel of the scope, which turns the flat polyp sessile, making it easier for snare resection (Figure 3).

Knowledge of these characteristics of various flat and serrated lesions is important for the practicing endoscopist to allow for improved detection and characterization of these colorectal lesions. More importantly, current artificial intelligence systems lack the ability to specifically recognize flat lesions based on biologic chromoendoscopy and, thus, the human eye and brain need to stay cognizant of the features of these lesions to identify them.

Images courtesy of EndoCollab. See endocollab.com for more information, including videos, quick tips, and lectures on these and many other practical endoscopy tricks.