CHICAGO—It is not clear why, but whole-gut transit time is longest for people living in Spain and shortest for those residing in India, according to results of an international study. WGTT also is significantly associated with age, sex and body mass index, according to the “Blue Poop Challenge,” a citizen scientist project involving 21,541 volunteers in 17 countries on five continents.

“In the largest study [of its kind,] we found that country-specific differences in WGTT remained significant after adjustment for age, sex and BMI,” said Will Bulsiewicz, MD, a gastroenterologist and the U.S. medical director of ZOE Global, a personalized nutrition company based in Boston. “The data suggest that WGTT varies according to nation of origin,” he added.

WGTT influences gut microbiota composition and is an indicator of gut health, according to Dr. Bulsiewicz. Disturbances in WGTT are linked to several digestive and metabolic diseases, but little is known about its population characteristics, he said, noting that “faster is typically better.”

A previous study in 1,102 participants by ZOE investigators found that “longer WGTT was associated with more visceral fat and higher postprandial glucose and triglycerides, independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Bulsiewicz added.

Tracking Movements in Blue

In the Blue Poop Challenge (joinzoe.com/bluepoop), the researchers examined how WGTT, measured by the blue dye method, was correlated with various factors in a large international population. Findings were based on self-reported WGTT after volunteers consumed blue muffins (84.5 g per muffin x 2, each containing 0.75 g of blue food coloring paste). WGTT was defined as the time elapsing between muffin ingestion and first appearance of blue color in the stool. Participants were predominantly female, young- to middle-aged and normal to slightly overweight (BMI, 22.3-26.3 kg/m2).

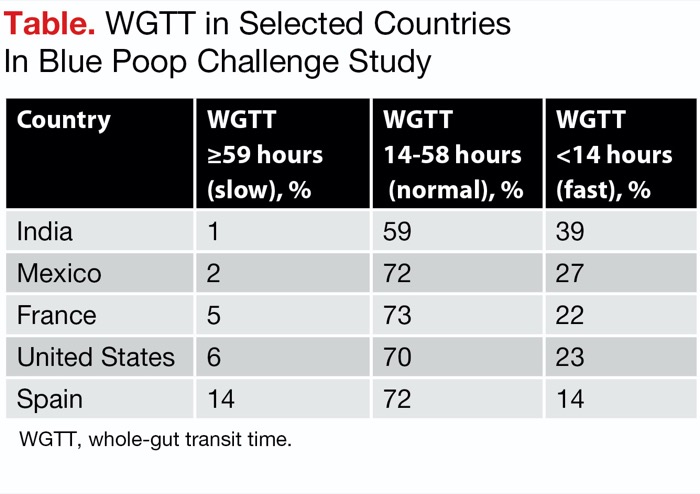

The mean WGTT was 23.9 hours (range, 16.2- 32.0 hours), with country-specific differences, said Dr. Bulsiewicz, reporting the findings at Digestive Disease Week 2023 (abstract Su1612). The longest WGTT, 28.0 hours (range, 21.7-45.8 hours), was reported in Spain and the shortest, 19.9 hours (range, 9.3-25.0 hours), was reported in India (P<0.001).

“In India, they are pooping the fastest. Nearly 40% of volunteers see blue poop in less than one day. In Spain, they poop the slowest. Is it the high-fat diet or eating at 10 p.m. that’s responsible for slow transit in Spain? That we don’t know. But if I had to guess why India has faster WGTT, I’d say it’s fiber related,” Dr. Bulsiewicz said. He noted that the Indian diet typically contains lots of lentils and few animal products or ultra-processed food.

The Table shows the extremes, along with figures for the United States and a few other countries.

| Table. WGTT in Selected Countries In Blue Poop Challenge Study | |||

| Country | WGTT =59 hours (slow), % | WGTT 14-58 hours (normal), % | WGTT <14 hours (fast), % |

|---|---|---|---|

| India | 1 | 59 | 39 |

| Mexico | 2 | 72 | 27 |

| France | 5 | 73 | 22 |

| United States | 6 | 70 | 23 |

| Spain | 14 | 72 | 14 |

| WGTT, whole-gut transit time. | |||

In an additional analysis of the two countries with the most participants—the United States, with 8,546 volunteers, and the United Kingdom, with 7,571—researchers found faster WGTT to be associated with older age (P<0.001) and lower BMI (P<0.001).

WGTT was longer in female than male participants (23.8 vs. 22.0 hours), and, by BMI, in obese versus normal-weight female (24.0 vs. 23.2 hours) and male participants (22.8 vs. 21.4 hours). Country-specific differences in WGTT remained significant (P<0.05) after adjustment for age, sex and BMI.

Dietary Factors Associated With Faster Transit

In the U.S. subset, the researchers also looked at dietary components within the context of slow, normal or fast transit time (abstract Su1615). Participants completed a U.S.-adapted version of the Leeds Short-Form Food Frequency Questionnaire, which captures the intakes of 20 food groups and was used in computing diet quality indices with the healthful plant-based index and Diet Quality Score. WGTT was separated into fast (<14 hours), normal (14-58 hours) and slow (=59 hours) times.

Fast and slow WGTTs were significantly associated with less healthful diet quality compared with normal WGTT (P<0.001). “Lower intakes of plant-based foods were associated with abnormal transit times, which is consistent with the known effect of dietary fiber,” Dr. Bulsiewicz said. “To me, the message is to elevate your entire dietary quality. It’s not a revolutionary concept, but we need more fiber.”

Blue Poop as Research Aid

Baha Moshiree, MD, MSc, a clinical professor of medicine at Wake Forest University and the director of motility at Atrium Health, in Charlotte, N.C., noted that the simple blue poop test has facilitated some important findings about the microbiome.

Investigators at King’s College, for example, found that gut transit time, measured via the blue dye method, was a more informative marker of gut microbiome function than traditional measures of stool consistency and frequency in a study of 863 healthy individuals (Gut 2021;70[9]:1665-1674). The blue dye test also predicted postprandial lipid and glucose responses as well as visceral fat.

As for the Blue Poop Challenge study, Dr. Moshiree said she found it interesting that female sex and obesity were associated with slower transit because wireless motility capsule testing has not found this to be so. “But more females than males have gastroparesis, a condition with delayed stomach transit,” she noted.

Although the role of diet, and fiber in particular, in gut transit has long been established, Dr. Moshiree said the current study “illustrates this finding among several countries with presumably different diets—suggesting again that a high-fiber diet leads to improved, or faster, gut transit times.

“Studies like this are actually very helpful, providing evidence [that] a healthier diet for us in the U.S.—perhaps ... the Mediterranean, high-fiber, high-herb diet is the way to go,” she commented.

Dr. Moshiree and her team are using blue muffin testing to evaluate gut transit and motility in children with neurodevelopmental disorders such as autism. The aim is to determine if changes in the gut microbiome and abnormalities of transit time influence behavior and neurologic manifestations of such diseases. (Visit the Pediatric GI section on our website for more on the bidirectionality of autism and GI conditions.)

—Caroline Helwick

The study was supported by Zoe Global Ltd. Dr. Bulsiewicz is employed by the company. Dr. Moshiree reported a U.S. patent, No. 63/283,665 for blue muffin transit studies (filed Nov. 29, 2021).

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}