Section Editors

University of Washington School of Medicine

Seattle, Washington

Universidad de la Republica Uruguay

Carilion Memorial Hospital

Roanoke, Virginia

Contributors

Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine

Roanoke, Virginia

Gastric antral vascular ectasia (GAVE), often called watermelon stomach, is an uncommon but important cause of gastrointestinal bleeding and anemia that was first described about 70 years ago.1

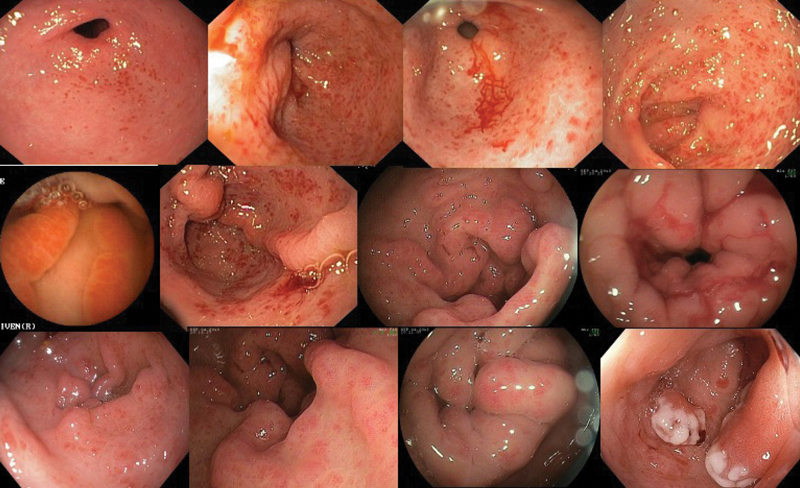

Watermelon stomach is mostly a misnomer because GAVE has a broad endoscopic appearance that includes linear, honeycomb, nodular, polypoid, giant folds, and mixed types (Figure 1). It can be represented by red spots, organized in stripes radiating from the pylorus (watermelon stomach), patchy gastritis, diffuse antral subepithelial hemorrhages and erythema (honeycomb stomach), nodules, polyps, and/or enlarged folds in the antrum.

The diagnosis of GAVE often is missed, likely because of a focus on searching for a watermelon stomach appearance. Histology shows dilation of mucosal capillaries, with focal thrombosis and fibromuscular hyperplasia of the lamina propria, and thickened mucosa with tortuous submucosal venous channels. The exact cause of GAVE is not known. Frequently, GAVE is associated with conditions including portal hypertension, cirrhosis, hypergastrinemia, metabolic syndrome, chronic renal failure, collagen vascular diseases, scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s disease, primary biliary cholangitis, bone marrow transplantation, pernicious anemia, and, as shown by our group, heart failure with left ventricular assist device and development of Heyde syndrome.

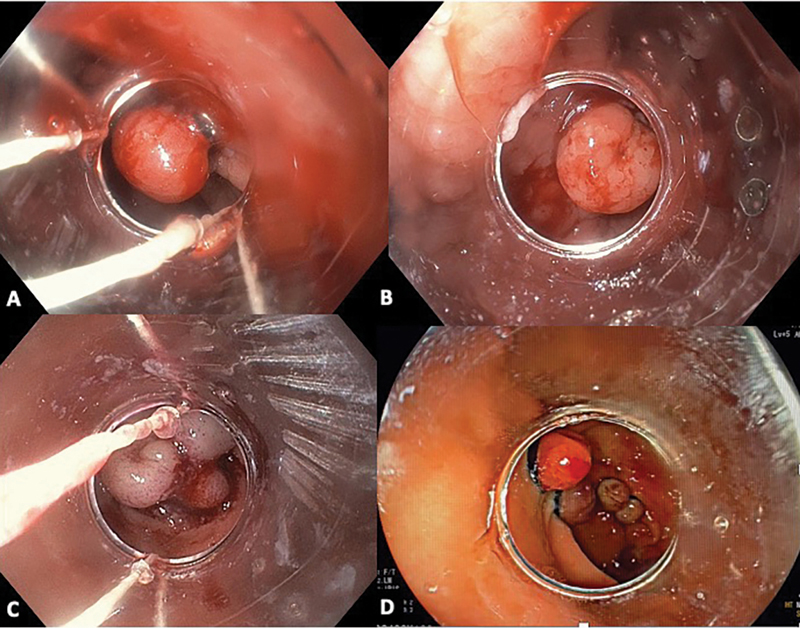

Treatment of GAVE is aimed at obliterating all the vessels and has been accomplished traditionally using argon plasma coagulation and more recently using radiofrequency ablation. Endoscopic band ligation (EBL) also has been demonstrated to be an efficient way to treat GAVE, especially the nodular form, that results in more rapid eradication of the syndrome and reduces requirement for blood transfusion (Figure 2).

Our tips on performing EBL for GAVE are the following:

- start distally;

- avoid placing too many bands close to the pylorus;

- place bands in a cork-like, semi-circumferential manner, from the pylorus to proximal antrum;

- place up to 12 bands per session;

- at the pylorus, band at most half of the luminal circumference to prevent inflammatory or fibrotic gastric outlet obstruction;

- use oral proton pump inhibitors for 4 to 6 weeks after banding for ulcer healing; and

- if iron deficiency is present, consider replacement with intravenous iron.

Reference

- Rider JA, Klotz AP, Kirsner JB. Gastritis with veno-capillary ectasia as a source of massive gastric hemorrhage. Gastroenterology. 1953;24:118-123.

Images courtesy of EndoCollab. See endocollab.com for more information, including videos, quick tips and lectures on these and many other practical endoscopy tricks.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}