Liver disease is a common cause of malnutrition in adults and children. Understanding common nutrient deficiencies, using the right nutrition assessment tools, and ensuring appropriate nutritional therapy is crucial to optimize care in these patient populations.

“Liver disease is quite prevalent and has a significant impact on nutritional status,” noted Jeanette Hasse, PhD, RD, the transplant nutrition manager at Baylor University Medical Center’s Baylor Simmons Transplant Institute, in Dallas. “We see profound malnutrition in these patients every day. With decompensated cirrhosis and malnutrition, there is an interaction: The cirrhosis leads to the malnutrition, but the malnutrition also complicates some of the problems associated with cirrhosis, such as hepatic encephalopathy.”

Malnutrition in patients with chronic liver disease is also associated with more complications and reduced survival among those who undergo surgery and those with hepatocellular carcinoma, as well as increased mortality for those waiting for liver transplant, Dr. Hasse noted in a webinar for the American Society for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition’s 2022 Malnutrition Awareness Week.

Nutrition Screening Tools

To identify the risk for malnutrition in these patients, Dr. Hasse recommended two liver disease–specific screening tools: the Liver Disease Undernutrition Screening Tool (LDUST) and the Royal Free Hospital-Nutritional Prioritizing Tool (RFH-NPT).

LDUST consists of six questions related to appetite, weight loss, muscle wasting and activity, with answers recorded in columns A, B or C. If a patient’s responses to two or more questions fall into columns B or C, they should be referred for nutrition assessment.

RFH-NPT is a three-step scoring flowchart. In the first step, patients with acute alcoholic hepatitis and those who are tube fed are automatically categorized as at high risk for malnutrition. The second step assigns numerical values to answers to questions related to fluid overload, weight loss and reduced dietary intake. Patients who receive a score of 0 are assigned routine clinical care; those with a score of 1 have their food charts monitored and are encouraged to eat; those with scores of 2 to 7 are referred to a dietitian for a full nutritional assessment.

Dr. Hasse also recommended using an objective test for frailty, such as the three-part Functional Assessment in Liver Transplantation’s Liver Frailty Index, which assigns a score based on hand grip strength, the time it takes to do five sit-to-stand chair stands (normally about 12 seconds), and how long the patient can hold three balance positions.

“In a physical assessment of a patient with liver disease, you will be looking for disease-specific clues,” she said. “For instance, are they jaundiced? Do they have icteric sclerae? Because of changes in hormones, sometimes they develop spider angiomas, palmar erythema and gynecomastia. Asterixis, a flapping tremor in the hands, could indicate encephalopathy. ...We are looking for ascites, muscle wasting and edema as well.”

The type of liver disease the patient has should be considered in the nutritional assessment as well, Dr. Hasse said. “If they have fatty liver disease, I think about insulin resistance, diabetes and obesity. If they have a cholestatic liver disease like primary sclerosing cholangitis or primary biliary cirrhosis, often those patients have inflammatory bowel disease and they can also have fat malabsorption, so you need to key in on fat-soluble vitamin deficiencies.”

Causes and Management Of Malnutrition

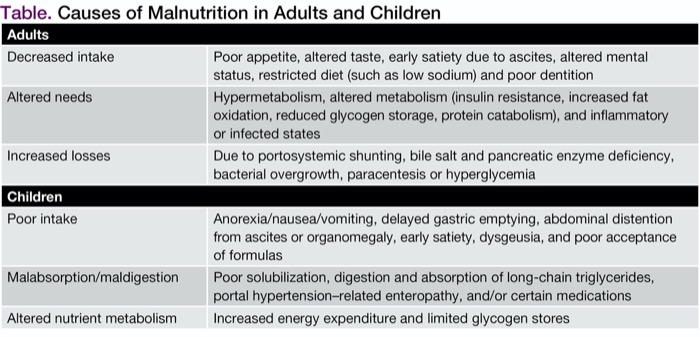

The causes of malnutrition in patients with liver disease fall into three main types (Table), according to Dr. Hasse. The longer the patient has had chronic liver disease, the more likely they are to have nutritional deficiencies, she said.

| Table. Causes of Malnutrition in Adults and Children | |

| Adults | |

|---|---|

| Decreased intake | Poor appetite, altered taste, early satiety due to ascites, altered mental status, restricted diet (such as low sodium) and poor dentition |

| Altered needs | Hypermetabolism, altered metabolism (insulin resistance, increased fat oxidation, reduced glycogen storage, protein catabolism), and inflammatory or infected states |

| Increased losses | Due to portosystemic shunting, bile salt and pancreatic enzyme deficiency, bacterial overgrowth, paracentesis or hyperglycemia |

| Children | |

| Poor intake | Anorexia/nausea/vomiting, delayed gastric emptying, abdominal distention from ascites or organomegaly, early satiety, dysgeusia, and poor acceptance of formulas |

| Malabsorption/maldigestion | Poor solubilization, digestion and absorption of long-chain triglycerides, portal hypertension–related enteropathy, and/or certain medications |

| Altered nutrient metabolism | Increased energy expenditure and limited glycogen stores |

The focus of treating malnutrition in patients with liver disease should be “food first,” Dr. Hasse said. “Try to get the patient to maintain a high-calorie, high-protein and usually low-sodium diet, with small, frequent meals. A bedtime snack is really important to prevent morning hypoglycemia and to decrease proteolysis overnight. Liberalize the diet if you can, and choose nutrient-dense foods. Have the patient use oral supplements, whether homemade or commercial. There may be a role for branched-chain amino acids, to help build muscle but also in patients with refractory encephalopathy. We do use appetite enhancers quite frequently with our patients, and will use tube feeding as well, usually a smaller-bore nasal enteric tube to be more comfortable.”

Complications and comorbidities can affect clinical decision making about nutritional management. “If I have a patient who has encephalopathy, they may not remember to eat, or they may not be [able] to cook at home. If they have varices and just had them banded, they may have difficulty swallowing,” Dr. Hasse noted. “Comorbidities like diabetes, celiac disease and ulcerative colitis will also influence your choices about nutrition therapy.”

Liver Disease–Related Malnutrition in Children

In the pediatric population, cholestatic liver disease—caused by reduced bile formation or flow resulting in decreased concentration of bile acids in the intestine and retention of biliary substances in the blood and liver—affects one of every 2,500 full-term infants. “These disorders are the most prevalent type of end-stage liver disease in children and are most commonly associated with malnutrition,” said Beth Scott, RD, a GI/liver transplant dietitian at Children’s Hospital Los Angeles. Common diagnoses include biliary atresia, choledochal malformations, disorders related to bile acid transport or synthesis, Alagille syndrome, and alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency.

“Any alteration in liver function can negatively impact nutritional status and increase a child’s risk for malnutrition,” Ms. Scott said. “When the liver is sick, nutrition is going to suffer. This is a common complication that increases morbidity and mortality.” About 39% to 80% of children with cholestasis have moderate to severe malnutrition, she noted (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;69[4]:498-511).

In children with end-stage liver disease who undergo transplant, optimizing nutrition can hasten post-transplant recovery and decrease complications. “We know that nutrition is the only pre-transplant intervention that can positively impact outcomes in this population,” Ms. Scott said.

Causes of malnutrition in children with liver disease, like the causes of malnutrition in adults with liver disease, fall into three categories (Table).

Identification of malnutrition in these infants and children should start with a detailed record of diet and feeding history. “If this is an infant, are they breastfed?” If they are, is the breast milk being fortified? Ms. Scott said.

“We need to know about the use of specialty formulas and modulars. In this time where we have so many formula shortages, we have patients who have been [given] multiple formulas, not as a result of intolerance but because they can’t get the formulas they may have been sent home on,” she noted. “We need to ask about preparation and concentration of formulas. When that is done incorrectly, it can cause some of the same GI side effects as inherent liver disease.”

Other topics for consideration are tolerance and feeding issues, introduction of solids and age-appropriate advances, nutrition support (what the regimen is and who is managing it), aversions and delayed feeding skills, and involvement of speech and other occupational therapists. “This is a critical step in planning for future transition back to oral feeding, which is always the goal,” she said.

Assessing Nutritional Status in Kids

Body weight is not the best marker of nutritional status in these children, Ms. Scott noted, because it can be affected by ascites, edema or organomegaly. Even upward weight trend lines are not reliable because they may reflect progressing liver dysfunction rather than improved nutrition. “Length/height and head circumference are appropriate indicators of chronic malnutrition, and it’s important to assess for stunting,” she said.

“Parameters that seek proportionality, such as weight/length and BMI [body mass index]/age parameters are not valid if weight is skewed by fluid status or organomegaly, which is going to be more often than not. It’s important to clarify in the documentation if what you see on exam is inconsistent with growth parameters,” she added.

An inexpensive, quick and accurate measure of nutritional status is anthropometry of the mid-upper arm circumference and triceps skinfold. “It is less affected by fluid status—thus a better measure of malnutrition—and is extremely useful in this population,” she said.

Electrolyte values can be expected to be abnormal in these children. “We expect to see some degree of hyponatremia, and frequently potassium alterations with the use of diuretics,” Ms. Scott pointed out.

“Serum proteins will be of limited value, but fat-soluble vitamins and essential fatty acids are going to be important because the majority of these patients will be deficient to some degree in one or all of these, especially if supplementation is not initiated early. Close monitoring of fat-soluble vitamins, particularly A, D, E and K, is warranted to adjust supplementation. If you have a patient whose liver issues resolve, it’s important to scale back the supplementation, or you can end up with some very high levels.”

What do these children need in terms of calories, protein and fluids? “In general, energy needs are 130% to 150% of estimated average requirements, with 40% to 60% coming from carbohydrates, 9% of total energy from protein, and 30% to 50% of total energy as fat—with 30% to 70% of those fats as medium-chain triglycerides and at least 40% as long-chain fatty acids to prevent deficiency,” Ms. Scott said. “We try to keep them to standard fluids based on weight, and keep the sodium intake on the lower end.”

Treatment and Progression of Feeding

Regarding treatment strategies, Ms. Scott recommended employing the algorithm on nutrition support of children with chronic liver diseases from the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition, published in 2019 (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;69[4]:498-511). “[The algorithm] gives guidance on how to progress through the stages of oral, enteral and parenteral feeding,” she said. “In general, we’re going to move from one step to the next using the guideliness.”

Ms. Scott recommeded “a low threshold for initiating nutrition support, given the strong association between malnutrition and poor outcomes. At every stage, we want to consider how to preserve or promote oral feedings and involve the parents in the decision.”

Principles for oral feeding in infants include fortifying breast milk, using formulas rich in medium-chain triglycerides, increasing concentration, using modulars and offering small, frequent feedings. For children, portion sizes should be increased when possible, bedtime snacks and nutritional supplements should be added, and, again, small, frequent feedings are recommended.

“Potential pitfalls include decreased appetite, nausea and vomiting, early satiety, and intolerance to volume, and these can be expected to get worse as the disease progresses,” Ms. Scott said. In addition, parental anxiety can promote a negative feeding environment.”

When an infant or a child must be transitioned to enteral feeding, a nasogastric tube is typically the first choice, she said. “You want to allow oral feeds during the day as much as possible, and provide nighttime drip feeds, but patients may require continuous drip feeds due to tolerance issues or concern for hypoglycemia. If this fails, we then advance to parenteral nutrition, where the energy needs are lower and mirror those of non-cholestatic children.”

The move to parenteral nutrition raises a number of questions and risk-benefit analyses. “There is an increased risk of infection and metabolic complications, and we need to make sure that the family is able to take care of the child safely,” Ms. Scott noted.

Don’t Lose Sight of Nutritional Issues

Malnutrition often is overlooked as an issue in patients with liver disease, said Carolyn Newberry, MD, an assistant professor of medicine and the director of nutritional services in the Innovative Center for Health and Nutrition in Gastroenterology at Weill Cornell Medical Center, in New York City, who moderated the session. “Risk stratification in these patient populations is very important. They are at high risk for being malnourished from a muscle wasting perspective, a nutrient deficiency perspective, and an excessive weight loss perspective. But because they are so medically complicated and there are so many other things to worry about with decompensations of liver disease, people can lose focus on nutrition. We cannot neglect it, however, because malnutrition is associated with significant morbidity and mortality in people with liver disease.”

—Gina Shaw

Dr. Hasse reported financial relationships with Alcresta and Nestlé. Dr. Newberry reported financial relationships with Baxter and InBody. Ms. Scott reported no relevant financial disclosures.

{RELATED-HORIZONTAL}