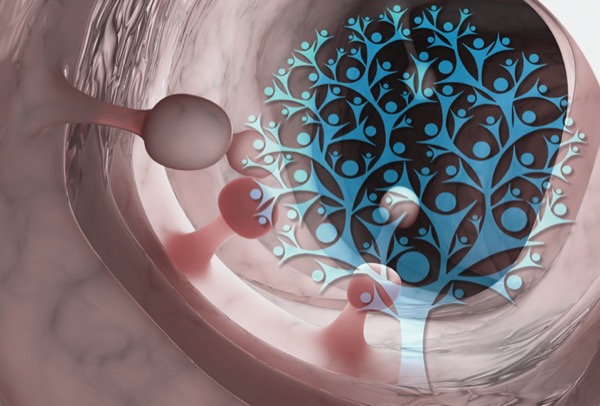

You ask your new patients if they have a family history of colorectal cancer, but do you ask them about a history of polyps? Maybe you should.

A new study has found that siblings and children of people with colorectal polyps are at a significantly increased risk for CRC, particularly when such lesions occur in more than one first-degree relative (FDR) or before the age of 50 years. The association remained significant after adjusting for family history of CRC.

“Our findings suggest that early screening may be tailored for first-degree relatives of individuals with polyps, particularly those with multiple first-degree relatives having a history of polyps and whose first-degree relatives’ polyps were diagnosed at a younger age,” said Mingyang Song, MBBS, ScD, an assistant professor in the Departments of Epidemiology and Nutrition at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, in Boston.

Dr. Song and his colleagues from Norway and Sweden reported the findings at the 2021 virtual Digestive Disease Week (abstract 82) and published the study in the British Medical Journal (2021;373:n877).

Previous data indicating an association of CRC with family history of polyps have been inconsistent, according to Dr. Song. Current guidelines recommend that individuals with a family history of advanced adenomas be screened earlier than those without, but these recommendations are considered weak and based on low-quality evidence, he said.

The new study used a Swedish registry to identify 68,060 people with CRC who were matched with 333,753 controls from the general population. For these roughly 401,000 individuals, FDRs were found through the country’s multigeneration register, and they were linked to a histopathology database that also included sublocation, year of diagnosis and age of FDR at polyp diagnosis.

The researchers calculated CRC odds ratios using three different models and estimated CRC incidence based on national data.

Risk Correlated With Family History of Polyps

The prevalence of at least one polyp in an FDR was 7.7% among cases and 5.3% among controls; advanced polyps accounted for 3.2% and 1.9% of lesions, respectively. The prevalence of CRC in an FDR was 10.4% for cases and 6.4% for controls.

Compared with individuals without a positive family history, those with an FDR with any polyp had a 62% increased risk for CRC on multivariable analysis and a 40% increased risk when the analysis adjusted for family history of CRC. The presence of an advanced polyp increased these risks to 76% and 44%, respectively, Dr. Song’s group found.

Two scenarios further enhanced this risk: the presence of at least two FDRs with polyps, which increased risk by 70% compared to no affected close relation, and diagnosis of a polyp in a near relative before age 50, which increased the risk by 77%.

“The risk elevation was more prominent for early-onset CRC and heightened by the coexistence of a family history of CRC,” Dr. Song said. “Given the increasing incidence of early-onset CRC, this family history is valuable data to integrate. Perhaps we introduce earlier screening for individuals with a family history of polyps.”

The registry information lacked data on the size of the polyps; therefore, the study could not address risk associated with small polyps. “This question needs further study, but based on the literature, it’s unlikely that a history of small polyps would increase risk notably,” he said.

A family history of serrated polyps appeared to be strongly associated with the risk for proximal colon cancer, but not distal colon or rectal cancer, Dr. Song added.

‘Tough to Get’ Polyp History, But Important

Mohit Girotra, MD, a consultant gastroenterologist and therapeutic endoscopist at Swedish Medical Center, in Seattle, agreed that obtaining a family history of polyps is difficult but should be strongly encouraged.

“Most patients may not know the exact type and size of polyp their family member had, but may be able to tell if their family member was advised repeating colonoscopy at three or five years versus 10 years, which is a subtle hint toward the polyp type,” Dr. Girotra said.

Sonia Kupfer, MD, an associate professor and the director of the GI Cancer Risk and Prevention Clinic at the University of Chicago, said the new study “showed similar overall trends to what has been previously reported, including increased risk with increasing numbers of affected individuals as well as younger ages at diagnosis. Of note, in this study, family history of serrated polyps was a risk factor specifically for proximal colon cancer.”

Dr. Kupfer said she sees room for improvement in incorporating polyp history into screening recommendations. In a recent survey of 137 patients who had undergone polypectomy, 40% said they believed their polyps placed their near relatives at increased risk for CRC, but only 7.3% of their endoscopists made recommendations for screening family members (Dig Dis Sci 2020;65[9]:2542-2550).

“This suggests areas for quality improvement to help inform individuals with familial CRC about their risks,” Dr. Kupfer said. “While it’s tough to get a polyp history, family history is still one of the best risk stratification tools we have.”

—Caroline Helwick

Drs. Girotra, Kupfer and Song reported no relevant financial disclosures.