The debate over routine versus selective intraoperative cholangiography (IOC) during laparoscopic cholecystectomy dates back almost to the origins of the procedure itself. One should first consider that today most surgeons practice selective cholangiography, which means that many use it infrequently. There are several reasons why IOC should be used at least liberally in clinical practice: 1) it is an important and unique skill component of cholecystectomy and surgeons need to be facile with the technique so it can be reliably performed; 2) it enables accurate interpretation of cholangiogram findings; 3) it may help identify aberrant biliary anatomy; 4) it is essential for identification of common bile duct (CBD) stones intraoperatively and a prerequisite for performing laparoscopic CBD exploration; and 5) it may reduce both the incidence of biliary injury and the severity of the injury (i.e., avoiding excision of a segment of the CBD when an injury has occurred).

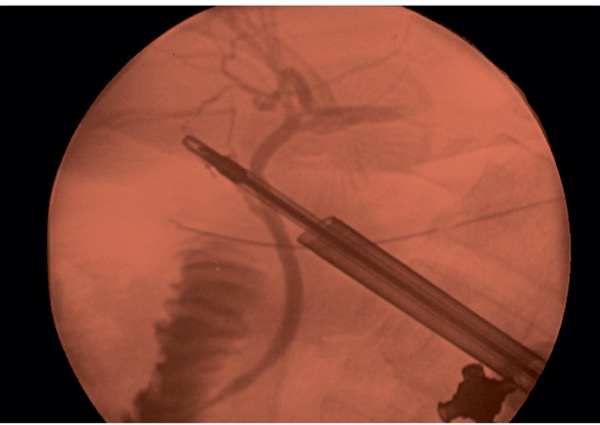

The ability to perform IOC is an essential skill that all surgeons who perform cholecystectomy should have in their armamentarium. IOC requires an incision in the cystic duct and cannulation with a small catheter, which can be challenging in some patients due to cystic duct valves. The ability to do IOC consistently and efficiently requires, at least at some point in one’s practice, having done it numerous times and under varying circumstances of gallbladder pathology. The reality, however, is that selective cholangiography in most surgeons’ practices means it is infrequently done. Selective cholangiography should also mean that it is routinely done in situations in which the patient is at increased risk for having a bile duct stone (ie, dilated CBD, abnormal liver function tests preoperatively, stones found in the cystic duct at operation, and a history of gallstone pancreatitis). One could also strongly argue that it should be done routinely in patients who have had a gastric bypass because of the altered anatomy that may preclude postoperative endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Since biliary anatomy has many variations, frequent use of IOC enhances recognition of aberrant anatomy (e.g., aberrant right posterior hepatic duct) as well as CBD stones. It can also lead to recognition that the CBD has been mistakenly dissected, thus avoiding a higher level of injury.

With the advent of LC, surgeons have largely abandoned management of CBD stones. However, several studies have shown that one-stage management of CBD stones at the time of LC is more cost-effective and may result in fewer adverse events than use of postoperative ERCP with its attendant risks for pancreatitis and other complications.1-3 Further, many community hospitals may not have ready access to postoperative ERCP. Facility with cystic duct cannulation and assessment for CBD stones is essential for surgeons who want to perform laparoscopic CBD exploration.

The role of IOC in prevention of bile duct injury was examined in detail by the recent consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy.4 Randomized controlled trials have been underpowered to address this question, but large administrative database studies have, more often than not, shown an association of use of IOC with a reduction in the incidence of biliary injury. In the consensus analysis of 14 large studies involving more than 2.5 million patients, the use of IOC was associated with a reduction in bile duct injury in both unadjusted (odds ratio [OR], 0.78; 95% CI, 0.63-0.96) and risk-adjusted analyses (OR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.62-1.07). However, many of these studies have a moderate or high risk for bias. In the Swedish National Gallriks database study of more than 51,000 cholecystectomies, the use of or intent to use IOC was associated with a reduction in bile duct injury in acute cholecystitis only.5 The guideline panel recommended that in patients with acute cholecystitis or a history of acute cholecystitis, IOC should be used liberally to mitigate the risk for bile duct injury.4 No recommendation was made for elective cholecystectomy due to uncertainty of the evidence. For surgeons with appropriate expertise, laparoscopic ultrasound is an alternative to IOC.

A strong recommendation from the consensus was that IOC should be used in cases with uncertainty of biliary anatomy or suspicion of biliary injury. In the consensus review of nine studies that addressed this question, IOC was significantly associated with increased intraoperative detection of bile duct injury (OR, 2.92; 95% CI, 1.55-5.68; P=0.014).

What about near-infrared cholangiography (NIRC)? Certainly, NIRC has promise and is easy to use, but it has not been widely studied outside of selected centers, or in large numbers of patients with obesity, acute cholecystitis or other difficult gallbladder scenarios. The technology for NIRC also has not yet widely penetrated throughout hospitals worldwide. In the consensus review, current evidence was found to be insufficient to make a recommendation regarding comparison to IOC. Compared with white light, including the study from Dr. Raul Rosenthal’s group,6 as expert opinion, we recommended that NIRC could be a useful adjunct to standard white light alone (conditional recommendation, low certainty of evidence), but should not be a substitute for good dissection and identification technique.4 It should also be noted that NIRC does not assess the bile duct for presence of stones.

So, what to conclude? In my own practice, I perform IOC routinely for all the reasons above, but I do not presume to recommend that all surgeons should take this approach. However, to perform IOC rarely or not at all, or not in a significant percentage of one’s cases, I would posit is a missed opportunity to identify unsuspected pathology, potentially reduce biliary injury risk, provide training for residents and maintain an important skill set. To do otherwise risks fostering an entire generation of surgeons who are lacking in this fundamental component of performing safe cholecystectomy.

References

- Berci G, Hunter J, Morgenstern L, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: first do no harm; second take care of bile duct stones. Surg Endosc. 2013:27(4):1051-1054.

- Bansal VK, Misra MC, Rajan K, et al. Single-stage laparoscopic common bile duct exploration and cholecystectomy versus two-stage endoscopic stone extraction followed by laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with concomitant gallbladder stones and common bile duct stones: a randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2014;28(3):75-85.

- Schwab B, Teitelbaum EN, Barsuk JH, et al. Single-stage laparoscopic management of choledocholithiasis: an analysis after implementation of a master learning resident curriculum. Surgery. 2018;163(3):503-508.

- Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, et al. Notice of duplicate publication [duplicate publication of Brunt LM, Deziel DJ, Telem DA, et al. Multi-society practice guideline and state of the art consensus conference on prevention of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2020;272(1):3-23; Surg Endosc. 2020;34(7):2827-2855.

- Tornqvist B, Stromberg C, Akre O, et al. Selective intraoperative cholangiography and risk of bile duct injury during cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102(8):952-958.

- Dip F, LoMenzo E, Sarotto L, et al. Randomized trial of near-infrared incisionless fluorescent cholangiography. Ann Surg. 2019;270(6):990-999.

—Raul J. Rosenthal, MD, FACS, FASMBS

Clinical Professor of Surgery Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University, Ohio Chairman, Department of General Surgery Director, General Surgery Residency Program Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston