Last year was a roller-coaster for gastroenterology, from drug recalls to wellness trend mishaps. But what is the new year for if not starting fresh and promising your patient’s gut a new healthy beginning, while leaving all the drama behind in 2019. To help your patients, here’s a top 10 list of things they should not be doing to their gut in 2020.

10. Do not sequence your microbiome

Interest in the microbiome is soaring and rightfully so. Alterations in the microbiome have been linked to conditions such as inflammatory bowel disease, obesity and fatty liver disease. The clinical value of microbiome sequencing, however, has not caught up to the interest and demand of patients.

The microbiome is dynamic and changes with diet and medical interventions.1 Also, different methods of sequencing provide different results, even using the same raw data from the DNA sequencing instrument. In addition to needing improvement in technique, microbiome testing needs credible companies to push the technology along. UBiome was a leader in the field, partnering with leading research institutions such as Harvard, Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Stanford. But in 2019, a criminal investigation into UBiome’s billing practices led to its bankruptcy. Although public and research interest in the microbiome is tremendous, microbiome-based diagnostics have a long way to go before they can be considered accurate, interpretable and ready to be a routine part of clinical care.

9. Do not take Zantac

Who hasn’t been prescribing ranitidine for the past few years when fast-acting heartburn relief is needed for your patients? Well, it’s time to find an alternative. The FDA announced in 2019 that ranitidine contains an impurity called N-nitrosodimethylamine (NDMA), which is a probable human carcinogen.2 This is not the first alert we’ve seen for NDMA; the FDA said it has been investigating NDMA and other nitrosamine impurities in medications for blood pressure and heart failure.

8. Do not ignore rectal bleeding

Yes, bleeding from the rectum could be hemorrhoids, but it could also be a growing colon polyp or even worse. In 2019, we saw an increased emphasis on the concerning rise of young-onset colorectal cancer.3 The reason is likely multifactorial and interrelated, including such factors as being overweight, eating red and processed meats, smoking, lack of physical activity, alterations of the gut microbiome, and environmental triggers. This disturbing trend has led the American Cancer Society to change its recommendation of starting screening for CRC in average-risk people from 50 to 45 years.4 Although this shift has not yet been endorsed by other societies, it is being seriously considered. Regardless, patients should discuss any rectal bleeding with a gastroenterologist.

7. Do not get a fecal transplant—unless it is absolutely indicated

Have you seen the “South Park” episode on fecal transplants? 2019 was the year the media got excited about all things microbiome, and that includes fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). FMT is an evolving treatment for recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection, along with many other potential indications. In 2019, our enthusiasm for FMT was dampened when the FDA announced that two patients developed extended-spectrum beta-lactamase–producing Escherichia coli bacteremia after FMT.5 These patients, one of whom died, were in two different clinical trials but both cases were linked by genomic sequencing to the same stool donor. The incidents were a wake-up call to improve donor screening to limit infection transmission that could lead to devastating outcomes. Most likely a temporary setback, the FMT community will likely enact more stringent criteria and the popularity of FMT will continue to soar.

6. Do not use CBD oil

Cannabidiol (CBD) is everywhere. I can’t walk a few blocks in any city without seeing a CBD retail shop. What is CBD anyway? Over 60 cannabinoids are found in natural marijuana. Some, like delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), are psychoactive. Others, like CBD, have little psychoactive effect and little or no abuse potential. CBD has been touted for a wide variety of health issues, but the strongest scientific evidence is for childhood epilepsy. Cannabis may be effective in the management of symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).6 However, the few randomized controlled trials of cannabis or CBD in IBD patients have not demonstrated value in reducing inflammation activity. CBD has been shown to be beneficial in a mouse model of IBD, but this benefit has not been successfully reproduced in humans.7 With so many people putting themselves on it, at least the studies have demonstrated that CBD has a good safety profile. But before your patient decides to stop by one of the local wellness shops and pick up a sublingual CBD tincture, counsel them to hold off until stronger evidence is available.

5. Do not overuse PPIs

We live in an era of proton pump inhibitor overuse. They are among the highest-selling classes of drugs and often prescribed without a correct indication and for a long duration. This point was further highlighted in a study by Spechler et al, published in The New England Journal of Medicine in 2019.8 The randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn had a total enrollment of 366 patients. But the researchers were surprised to find that barely any of the patients they enrolled truly had PPI-refractory acid reflux! In fact, only 78 patients with true refractory heartburn underwent randomization and for them, surgery was found to be superior to medical treatment.

This study highlights the misuse of PPIs and need to use diagnostic tools, such as pH monitoring, to accurately identify acid reflux and treat it appropriately. If acid reflux is diagnosed, gastroenterologists should feel confident prescribing PPIs—especially after the prospective, randomized study published this year demonstrated no relationship between PPI use and the previously documented adverse events, other than enteric infections.9 Let’s hope there is less anti-acid drama in 2020!

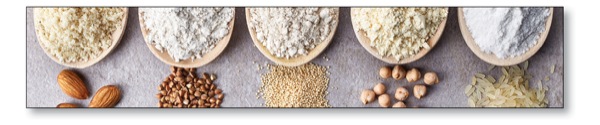

4. Do not go gluten-free ‘just because’

If your patient has any suggestive symptoms of celiac disease, non-celiac gluten sensitivity or wheat allergy, then they warrant an appropriate workup and consideration of a gluten-free diet. But for everyone else, counsel patients to think twice about going gluten-free for unsubstantiated health benefits. The consumption of gluten-free foods has significantly increased in the past years and billions of dollars are being spent on retail sales of gluten-free foods. The rise of the gluten-free diet has been driven by multiple factors, including media coverage, consumer-directed marketing, and reports in the literature and media of clinical benefits. A survey reported on National Public Radio found that almost one-third of American adults would prefer to reduce or avoid eating gluten altogether.

What all these gluten avoiders may not know is that there are multiple potential harms of being on a gluten-free diet, including micronutrients and fiber deficiencies and changes to the microbiome.10,11 Avoiding gluten may result in eating less beneficial whole grains, which has even been linked to coronary artery disease. So before your patient jumps on the gluten-free bandwagon, discuss the potential risks and benefits.

3. Do not use risky gastroparesis drugs

Our therapeutic arsenal for treating gastroparesis has been inadequate and riddled with side effects and limitations of short treatment durations. I pretty much stopped using metoclopramide, as few of my patients would consent to using it after I explained the boxed warning of often irreversible tardive dyskinesia. Therefore, I was thrilled when Florencia et al published a randomized placebo-controlled study on the use of prucalopride (Motegrity, Takeda) in idiopathic and diabetic gastroparesis.12 Prucalopride is a selective 5-hydroxytryptamine 4 receptor agonist that has been used for gut motility in Europe for the past 10 years. The study found that prucalopride significantly improved the total Gastroparesis Cardinal Symptom Index and the overall Patient Assessment of Upper Gastrointestinal Disorders–Quality of Life score. The gastric half emptying time was significantly enhanced by prucalopride compared with placebo and baseline (98±10 vs. 143±11 and 126±13 minutes; P=0.005 and <0.001, respectively). Although the FDA has yet to approve the drug for this indication, I anticipate its arrival soon and look forward to providing my patients with better options for gastroparesis.

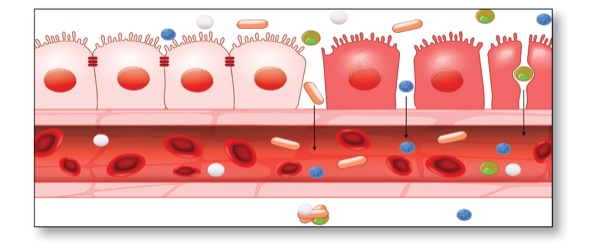

2. Do not get tested for leaky gut

The expression “leaky gut” has been getting a lot of attention in the media lately and many patients are starting to ask if they have it. It is important to understand that leaky gut—also known as increased intestinal permeability—is a real pathophysiologic phenomenon in which defects in the gut lining allow food, toxins and gut bugs to penetrate the tissues beneath.13 I often advise my patients that they certainly may have leaky gut if they have an underlying GI condition such as celiac disease or IBD. The key point is that leaky gut is always due to something, so looking for it with a lactulose/mannitol test has no clinical value. Instead, try to find the underlying gastrointestinal disorder that may be contributing.14

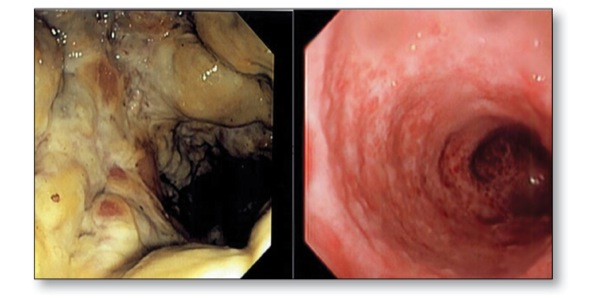

1. Hold the coffee enemas, please

On Gwyneth Paltrow’s website Goop, under “The Beauty and Wellness Detox Guide,” you can find a $135 Implant O-Rama System At-Home Coffee Enema. The website goes on to explain that “proponents argue that it’s crucial for moving things along, particularly because our systems are over-taxed by clearing the toxins of modern-day life.” As part of an “anticancer regimen,” coffee enemas have been touted “to help relieve pain, nausea and other symptoms accompanying detoxification.” Others claimed that caffeine is absorbed in the colon and causes vasodilatation in the liver, which enhances the toxin elimination. Luckily, we now know better than that. None of this has been proven and there is no evidence of the clinical efficacy of coffee enemas. In fact, coffee enemas are associated with severe adverse reactions, including a case of proctocolitis that was presented at the American College of Gastroenterology’s 2019 meeting.15 There are several pathways that could contribute to the adverse events of a coffee enema, including direct contact injury, damage from activation of inflammation and blood flow alteration. Leave the coffee enemas to Gwyneth and keep your patients’ colons healthy.

References

- Allaband C, McDonald D, VÁzquez-Baeza Y, et al. Microbiome 101: studying, analyzing, and interpreting gut microbiome data for clinicians. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(2):218-230.

- FDA. www.fda.gov/ news-events/ press-announcements/ statement-alerting-patients-and-health-care-professionals-ndma-found-samples-ranitidine. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Siegel RL, Fedewa SA, Anderson WF, et al. Colorectal cancer incidence patterns in the United States, 1974–2013. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109(8).

- American Cancer Society. www.cancer.org/ latest-news/ american-cancer-society-updates-colorectal-cancer-screening-guideline.html. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- FDA. www.fda.gov/ vaccines-blood-biologics/ safety-availability-biologics/ important-safety-alert-regarding-use-fecal-microbiota-transplantation-and-risk-serious-adverse. Accessed January 10, 2020.

- Picardo S, Kaplan GG, Sharkey KA, et al. Insights into the role of cannabis in the management of inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2019; doi:10.1177/1756284819870977

- Naftali T, Mechulam R, Marii A, et al. Low-dose cannabidiol is safe but not effective in the treatment for Crohn’s disease, a randomized controlled trial. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62(6):1615-1620.

- Spechler SJ, Hunter JG, Jones KM, et al. Randomized trial of medical versus surgical treatment for refractory heartburn. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(16):1513-1523.

- Moayyedi P, Eikelboom JW, Bosch J, et al. Safety of proton pump inhibitors based on a large, multi-year, randomized trial of patients receiving rivaroxaban or aspirin. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(3):682-691.

- Niland B, Cash BD. Health benefits and adverse effects of a gluten-free diet in non-celiac disease patients. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;14(2):82-91.

- Hansen LBS, Roager HM, SØndertoft NB, et al. A low-gluten diet induces changes in the intestinal microbiome of healthy Danish adults. Nature Comm. 2018;9(1):4630.

- Carbone F, Van den Houte K, Clevers E, et al. Prucalopride in gastroparesis. A randomized placebo-controlled crossover study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2019;114(8):1265-1274.

- Odenwald MA, Turner JR. The intestinal epithelial barrier: a therapeutic target? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;14(1):9-21.

- Sequeira IR, Lentle RG, Kruger MC, et al. Standardising the lactulose mannitol test of gut permeability to minimise error and promote comparability. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99256.

- Lee A, Kabashneh S, Rahim U, et al. A case of proctocolitis secondary to the use of coffee enema. Presented at: American College of Gastroenterology 2019 Annual Scientific Meeting; October 29, 2019; San Antonio, TX. Abstract P2000.

The views expressed in this article do not necessarily reflect those of the publication.