In the Transgender Surgery and Health Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, director Maurice Garcia, MD, currently has a two-year waitlist to perform gender-affirming operations.

Although there’s considerable demand for these procedures today, just five years ago, the landscape for gender-affirming procedures in the United States looked much different. Transgender patients had few options for surgical care and insurance companies did not cover the operations.

“At that time, most genital surgeries were done in private practices, under the radar, or patients would travel abroad where the costs for these procedures were typically much less,” Dr. Garcia said.

In 2013, Dr. Garcia became concerned about the quality of genital surgery, as he began seeing transgender patients with severe complications from phalloplasty and vaginoplasty procedures. Studies showed that complication rates for phalloplasty and vaginoplasty vary considerably—from 15% to 70%—depending on a surgeon’s technique and expertise (Am J Roentgenol 2014;203[2]:323-328; Clin Anat 2018;31[2]:191-199).

Eager to raise the level of care, Dr. Garcia went to England for a yearlong fellowship program at University College London to learn the standard approaches. When he returned to the United States in 2014, he established a gender-affirming surgery program at the University of California, San Francisco—one of the first such programs in the country.

“A lot of my earliest work in the field was the hardest,” Dr. Garcia said. “I was doing revision surgeries, fixing complications from botched operations. But from these challenging cases, I learned what works and what doesn’t.”

Ultimately, he hoped to develop techniques to minimize the complications from these complex procedures.

Last year, Dr. Garcia and colorectal surgeon Yosef Nasseri, MD, did just that.

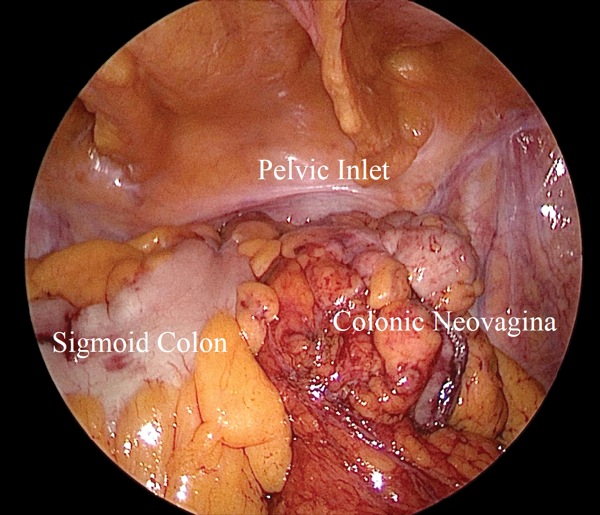

The surgeons had recently teamed up to perform several colovaginoplasty procedures but were eager to improve the technique. The procedure, which involves creating a neovagina from part of the colon, provides depth and lubrication similar to the vagina, but typically is used only as a salvage surgery when the standard penile inversion approach fails.

When performing a colovaginoplasty, surgeons historically used the sigmoid colon to form the neovagina because it is closest to the pelvis and often redundant, explained Dr. Nasseri, who practices with the Surgery Group of Los Angeles. However, using the sigmoid colon is tricky because the vascular anatomy varies from patient to patient. The inferior mesenteric vascular pedicle does not always reach far enough and the colorectal anastomosis has a high leak rate. Previous studies reported complications requiring revisional surgery in more than half of patients undergoing this procedure (Ann Plast Surg 2018;80[6]:684-691).

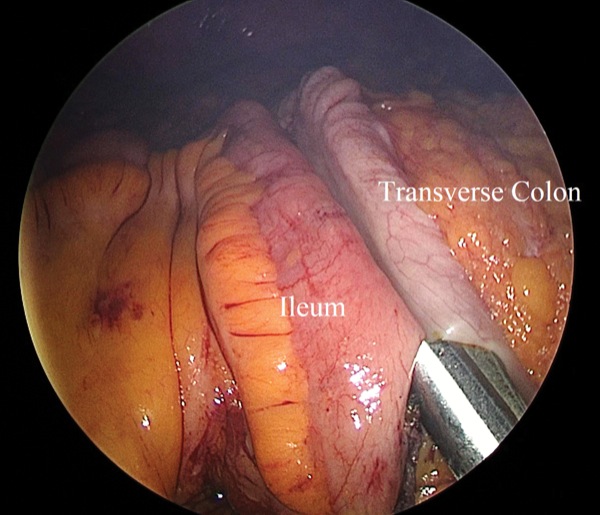

Dr. Garcia had an idea to mitigate these risks by using the right colon instead.

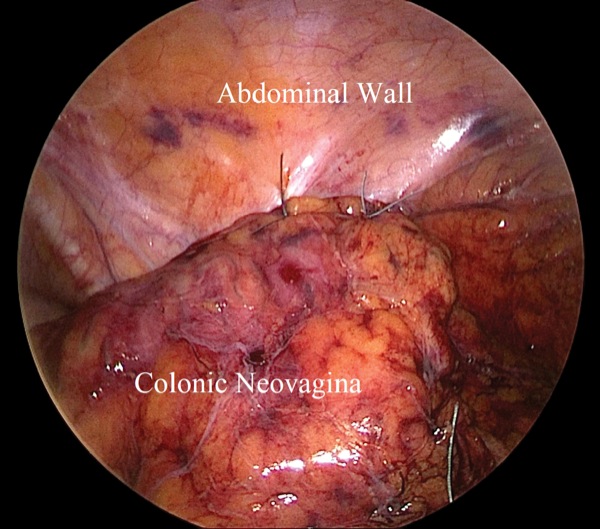

“Our initial roadblock was figuring out how to get the right colon to the pelvis, but we realized that if we flipped the right colon 180 degrees clockwise, it reached easily,” Dr. Nasseri said. “The procedure worked beautifully and was much simpler and safer than the standard colovaginoplasty technique.” Dr. Nasseri explained that the ileocolic anastomosis is safer because it has a low leak rate and is further from the pelvis, and thus does not impinge on the neovagina. The ileocolic vascular pedicle has advantages as well, because it comes with less anatomic variation and can more easily and reliably reach the deep pelvis.

The results so far are promising. Dr. Nasseri said none of their first 14 patients had a readmission within 30 days, and only three experienced complications requiring revision: two prolapsing neovaginas and one neovaginal stenosis. Given the minimal complications, they believe their technique could be a promising alternative to sigmoid vaginoplasty and even be performed as a primary operation instead of the penile inversion technique.

The duo presented their minimally invasive technique and experience with the 14 patients at several upcoming meetings, including the International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health in March, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons in April, and will do so again at the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons in June.

“This approach is a perfect example of the synergy that happens when surgeons who bring their own expertise come together,” Dr. Garcia said. “We all have to innovate, design new techniques and form unique collaborations to continue to advance the field.”

Evolution of Care

Loren Schechter, MD, a plastic surgeon based in Chicago, has watched the surgical landscape change radically since he first began providing care to transgender patients almost two decades ago.

“In the earlier days, it was difficult to find an institution that would allow us to perform gender-affirming surgeries, and insurance coverage was rare,” said Dr. Schechter, the medical director of The Center for Gender Confirmation Surgery at Weiss Memorial Hospital. “People would pay out of pocket and the cost was often too high to make surgery accessible to most.”

These procedures can have prohibitive costs. They typically range from $7,000 to $50,000, with some reaching six figures, according to estimates from the Transgender Law Center.

In the past few years, however, the demand for gender-affirming procedures has surged as societal attitudes have begun to change, insurance coverage has broadened and access to care has improved.

“We’ve gone from hospitals shutting the door in patients’ faces to hospitals around the country scrambling to start their own program,” Dr. Schechter said.

A watershed moment for transgender patients occurred in 2014, when one of Dr. Schechter’s patients, Denee Mallon—a 74-year-old transgender woman—challenged Medicare’s 1981 ban on covering gender-affirming surgery. The Department of Health and Human Services decided to remove the ban, an action that ultimately opened the door for insurance companies to begin covering the operations.

“This decision opened a floodgate,” said Randi Ettner, PhD, a clinical psychologist and expert on gender identity, who is based in Illinois. “Previously, people who never dreamed they could afford surgery that was medically necessary now could.”

Since then, a handful of academic institutions across the United States—including Mount Sinai Hospital and New York University (NYU) in New York City, Hahnemann University Hospital in Philadelphia, Boston Medical Center, and Oregon Health & Science University in Portland—established their own programs.

However, surgery is only one component of care. The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH), which outlines the standards of care for transgender patients, highlights the need for an individualized approach to gender transition that may include counseling, hormone treatment and surgery (JAMA Surg 2017;152[4]:394-400).

“There’s no one-size-fits-all approach,” said Dr. Schechter, who serves on WPATH’s board of directors. “For instance, some people don’t identify as binary male/female, so it’s important to tailor care to meet a person’s unique needs and goals.”

Complications of Innovation

Surgeons often see transgender patients at the end of their journey of transitioning.

“By the time we see patients, they have often been on hormones and changed their names and gender on their birth certificates,” said Lee Zhao, MD, an assistant professor of urology and co-director of the Transgender Reconstructive Surgery Program at NYU Langone Health, in New York City. “The surgery is just to match their genitalia with their self.”

While at NYU in 2013, Dr. Zhao began seeing transgender patients with severe complications from their gender-affirming procedures.

“Some patients, for instance, had urine coming out of the wrong opening or weren’t able to urinate at all,” Dr. Zhao said. “When I reached out to the surgeons who had performed the original operations, they would tell me they preferred for me to take care of the complications. So I began performing reconstructive surgery to help these patients.”

A point came when patients would come to him before undergoing surgery elsewhere in anticipation of experiencing a complication, Dr. Zhao said. Eventually, patients started asking Dr. Zhao if he would perform their primary operations instead.

“That’s how my practice started,” said Dr. Zhao, who developed NYU’s program in 2016, with two plastic surgeons, Rachel Bluebond-Langner, MD, and Jamie Levine, MD. The program now has more than a dozen staff members, featuring a spectrum of specialties from adolescent medicine to vocal surgery.

Recently, his team developed new techniques to avoid those complications in the first place.

“I realized that some of the complications occurred because the operations require visibility in difficult-to-see deep spaces,” Dr. Zhao said. “I had already been using a surgical robot to fix the complications, so I developed a robotic technique to help prevent them.”

Dr. Zhao performs peritoneal flap vaginoplasty in combination with penile inversion surgery to achieve sufficient vaginal depth. The technique minimizes the disadvantages of the standard penile inversion surgery, such as the risk for stenosis of the vagina, hair within the vaginal cavity and injuries to the rectum. He recently described the technique and outcomes in the first 31 patients, noting only two complications (J Sex Med 2018;15[2 suppl 1]:S12-S13).

In addition, Dr. Zhao developed a robotic vaginectomy to prevent urinary complications common to phalloplasty. He and his colleagues described the technique and outcomes in 11 transgender men, reporting no perioperative complications and no patients who developed a urinary fistula or had difficulty voiding (J Sex Med 2018;15[2 suppl 1]:S13-S14).

The team performs three to four genital operations a week. This figure doesn’t factor in the most common gender-affirming surgeries, chest masculinization and breast augmentation, which Drs. Bluebond-Langner and Levine also perform. “We can’t keep up with the demand,” Dr. Zhao said, and like Dr. Garcia, he has a two-year waitlist just for genital surgery.

Training the Next Generation Of Providers

Even as surgical care improves and insurance coverage expands, meeting patient demand remains a challenge. Currently, the demand for gender-affirming surgeries far outstrips the supply of surgeons trained to perform them.

With an estimated 1.4 million adults in the United States who identify as transgender and only about a dozen programs dedicated to gender-affirming surgery, the need for more surgeons trained in the complex procedures and for better access to care for transgender patients is increasing.

“Transgender people may have poor health because they avoid going to the doctor after having bad experiences with providers in the past or because they fear being discriminated against,” said Dr. Ettner, who also is the secretary for WPATH. “But the literature shows that a person’s quality of life vastly improves after surgery.”

That is why some hospitals are creating fellowship programs to train the next generation of providers. Drs. Garcia and Schecter recently launched one-year fellowship programs for gender-affirming surgeries in their Los Angeles and Chicago institutions, respectively, as did surgeons at Mount Sinai Hospital and Hahnemann University Hospital. Dr. Zhao’s team incorporated training in gender-affirming procedures into NYU’s existing fellowship in reconstructive urology.

Dr. Schecter graduated his first fellow in August 2018, and is currently training the second, with a third one lined up for the following year. Dr. Garcia trained two plastic surgeons through the fellowship program so far.

“We have to commit to teaching these procedures, offering fellowship training and publishing our findings,” Dr. Garcia said. “My ultimate goal is to help the field of transgender medicine grow with the same attention to high standards that every other field of medicine enjoys.”

—Victoria Stern