Washington—Expanding on previous studies showing that the burden of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease is not equally distributed in the population, a new meta-analysis has identified significant racial and ethnic differences in the prevalence and severity of the disease in the United States.

“Hispanic patients have a disproportionately higher prevalence of NAFLD and black patients have a lower prevalence of NAFLD, despite higher rates of obesity and diabetes in [the latter] population,” said lead author Nicole Rich, MD, a fellow in the Division of Digestive and Liver Diseases at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas.

Dr. Rich and her colleagues conducted the meta-analysis to characterize racial and ethnic variation, severity and prognosis of NAFLD, which is the most common chronic liver disease in the world and affects an estimated 75 million to 100 million Americans. The investigators searched MEDLINE, EMBASE and Cochrane databases from their earliest entries to August 2016 for studies reporting NAFLD prevalence in population-based and high-risk cohorts, and its severity and prognosis. Dr. Rich said some studies contained data from overlapping cohorts, and in these cases, the researchers selected the most inclusive and/or most contemporary cohort for their analysis.

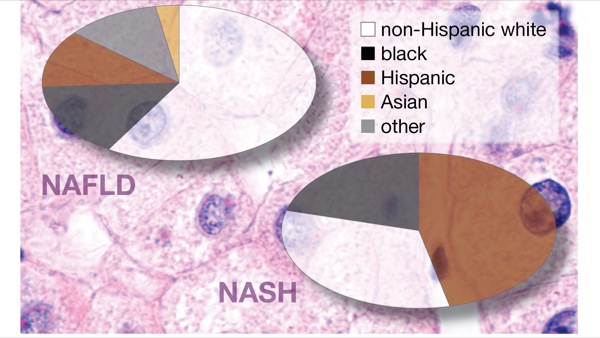

The final sample consisted of 34 studies with 368,569 unique patients: 16 studies of NAFLD prevalence, 18 studies of severity and six studies of prognosis. More than half of the patients—58.7%—were non-Hispanic white, 15.6% were black, 11.9% were Hispanic, 11.1% fit into the “other” category and 2.7% were Asian.

Reporting the findings at the 2017 Liver Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (abstract 57), Dr. Rich said NAFLD prevalence was higher in Hispanics than in whites in both population-based (relative risk [RR], 1.47) and high-risk (RR, 1.16) cohorts. The prevalence of NAFLD was lower in blacks than in whites in population-based (RR, 0.74) and high-risk (RR, 0.78) cohorts.

The prevalence of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) in patients with NAFLD was 31.4% overall, 45.4% in Hispanic patients, 32.2% in white patients and 20.3% in black patients. The risk for NASH was higher in Hispanics (RR, 1.09; 95% CI, 0.98-1.21) and lower in blacks (RR, 0.72; 95% CI, 0.60-0.87) than in whites. Roughly 20% of patients with NAFLD had significant liver fibrosis. The presence of significant fibrosis (stage F3-F4) was highest in whites (22.3%), lower in Hispanics (19.6%) and lowest in blacks (13.1%), but these differences were not statistically significant.

“When we looked at NAFLD outcomes, the studies reported heterogeneous outcomes, and we were not able to perform an analysis on that data,” Dr. Rich said.

Dr. Rich said genetics play a role in the differences and more studies are needed to develop strategies to reduce NAFLD disparities. “Black patients have a very high risk of obesity and diabetes but still have a lower risk of NASH, so there may be genetic protective factors at play,” she said.

According to Lisa VanWagner, MD, MSc, an assistant professor of medicine in the Division of Gastroenterology & Hepatology and Preventive Medicine at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine, in Chicago, the observation that NAFLD prevalence and NAFLD severity are highest in Hispanics and whites and lower in blacks is not new information. “What is new here is providing an estimate of the risk difference by pooling data that has been published across multiple studies,” said Dr. VanWagner, who was not involved with the study. She said clinicians can tell a patient, “If you are Hispanic, you have a 36% increased risk of having NAFLD and a 9% increased risk of developing NASH compared to someone who is not Hispanic. However, this study does not give us the [reason] why.”

Variation Likely More Than Genetic

The reason for the differences is complex and not completely understood. “We do have data that suggests that some of the observed differences between race and ethnicity in NAFLD and NASH severity is due to genetic differences, but studying racial variations purely using a genetic model to explain differences assumes that race is a biological category and that genes that determine race are linked with the genes that determine health,” Dr. VanWagner said. “Recent studies have shown that there is more genetic variation within race than between races and that race is more of a social construct than a biological construct.”

For example, Dr. VanWagner explained, in terms of ethnicity, “Hispanic” includes more than 400 million people from many different ethnic subgroups in more than 20 different countries. “Trying to interpret what differences due to ethnicity actually means is a challenge,” she said, noting that little published data exist exploring both ethnicity and race related to NAFLD. “Potential differences in NAFLD prevalence and NASH severity could be explained not just by genetics,” but also by differences in “socioeconomic status, access to health care … diagnosis, treatment and patient education/understanding about the disease,” she pointed out.

Dr. VanWagner emphasized that even though black race is associated with a lower risk for severe NASH, it does not mean that blacks do not get NASH. “For the practicing clinician, it is of paramount importance not to rule out NASH” just based on a patient’s race, she said. To “halt the NAFLD epidemic,” she concluded, “ensuring equitable care and improving access and delivery of care across all racial-ethnic populations is of utmost importance.”

—Kate O’Rourke

Drs. Rich and VanWagner reported no relevant financial conflicts of interest.