Chicago—Barrett’s esophagus has long been defined as intestinal metaplasia of the tubular esophagus, and is the most important risk factor for the development of adenocarcinoma. But the emergence of upper endoscopy has led to questions about where the esophagus ends—giving rise to a debate about whether Barrett’s esophagus also encompasses the most proximal part of the stomach beyond the gastroesophageal (GE) junction.

“We are assuming that the Barrett’s ends at the GE junction,” said Hassan A. Siddiki, MD, MS, of the Department of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at Mayo Clinic Arizona, in Scottsdale. “But that assumption has been challenged multiple times. There is a whole body of literature that doesn’t think the esophagus ends at the GE junction, and that the proximal few centimeters of the stomach is actually a dilated lower esophagus.”

At the American Gastroenterological Association’s 2016 James W. Freston Conference, Dr. Siddiki presented data showing that intestinal metaplasia often extends beyond the GE junction in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

He and his colleagues examined biopsies taken from the part of the gastric fold just beyond the GE junction in 460 consecutive patients undergoing esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD). Of these patients, 287 had known cases of Barrett’s esophagus, and 173 had no Barrett’s diagnosis and were undergoing EGD for other reasons, including gastroesophageal reflux disease, dyspepsia or chest pain.

An expert gastrointestinal pathologist, who was blinded to patients’ clinical indications, reviewed the biopsy samples for presence of cardiac mucosa and intestinal metaplasia in the cardiac mucosa. Overall, 377 of 460 patients (82%) who underwent EGD had cardiac mucosa. But the prevalence of cardiac mucosa was significantly higher in the group with Barrett’s esophagus, compared with those who underwent the procedure for other reasons (86% vs. 74%).

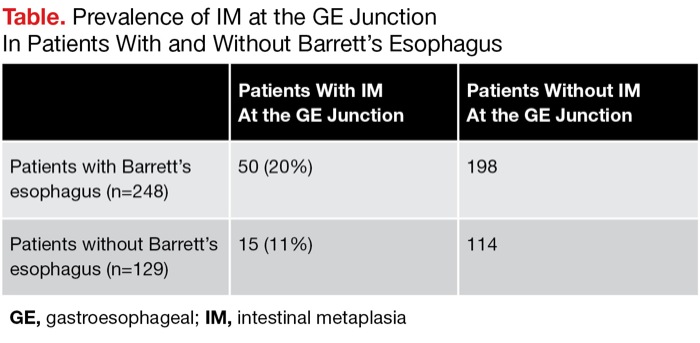

Patients with Barrett’s esophagus also had a significantly higher prevalence of intestinal metaplasia beyond the GE junction compared with those without Barrett’s esophagus (20% vs. 11%). More than one-fourth of the 50 patients with Barrett’s esophagus and intestinal metaplasia beyond the GE junction had signs of neoplastic progression, such as dysplasia and adenocarcinoma, Dr. Siddiki’s group reported (Table). None of the patients in the comparison group had these signs of progression.

| |||||||||||||||

The findings have important implications for current protocols for screening and surveillance, Dr. Siddiki said. “The injury that leads to Barrett’s proximal to the GE junction likely gives rise to similar pathology beyond it,” he said. “This challenges the current guidelines that we should not biopsy anything beyond the GE junction” in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

The observations are likely to fuel ongoing debate about the nature of the junction between the esophagus and stomach, which contains the cardiac mucosa.

“It’s an interesting observation that needs more confirmation,” said Stuart Spechler, MD, the Berta M. and Cecil O. Patterson Chair in Gastroenterology at UT Southwestern Medical Center, in Dallas. “We do see that the type of stomach cancers that involve the cardia are much more like esophageal cancers than distal stomach cancers, in terms of epidemiology and biologic behavior. It might be that the cardia area that we identify endoscopically is more like esophagus than stomach. There are even some data to suggest that the region that appears endoscopically to be the cardiac-lined proximal stomach actually is the esophagus.”

For now, Dr. Spechler said, the findings should not immediately change practice. “But we may need to rethink the guidelines in the future, if further studies support the findings,” he said.

Dr. Siddiki agreed it would be premature to begin routinely sampling beyond the GE junction.

“We don’t have enough data to say we should [routinely] start sampling beyond the GE junction,” he said. “The incidence of this cancer is quite low, which doesn’t justify universal sampling beyond the GE junction.”

If the findings are confirmed, it may also have implications for radiofrequency ablation of Barrett’s esophagus, Dr. Spechler said. He noted the GE junction is a frequent site of recurrence for intestinal metaplasia in patients with Barrett’s esophagus.

“It might be because this intestinal metaplasia extends down farther than we appreciate,” Dr. Spechler said.

—Bridget M. Kuehn