Over the 10-year period between 2005 and 2014, about 11,000 endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedures were performed in children in the United States, according to a new study that assessed national and regional trends in age-specific volumes and outcomes after ERCP in the pediatric population.

A strong relationship has already been established between volume and outcomes for advanced endoscopy procedures such as ERCP and endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) in adults, and the new study indicates a similar relationship in pediatric patients (J Pediatr 2021;232:159-165.e1). Approximately 60% of pediatric ERCPs were performed in urban teaching centers, about 34% in urban centers, and just 5% in rural hospitals, the authors found, and those performed in the higher-volume urban teaching and general urban centers were associated with significantly shorter durations of hospitalization than those performed at rural centers.

Experts believe that pediatric advanced endoscopy (PAE) cases are likely to become more common in the coming years. “We know there is a rise in incidence of pancreatic disease in children, and with that rise sometimes comes endoscopic treatment. We also know that, unfortunately, the obesity epidemic in America has produced increases in associated biliary and gallstone diseases in children,” said Quin Liu, MD, the director of the Advanced Endoscopy Fellowship Program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center (CSMC), in Los Angeles, and an assistant clinical professor of pediatrics and Medicine at CSMC and the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. “When my colleagues’ centers started doing advanced pediatric endoscopy procedures, they quickly saw their volumes increase.”

But even given these trends, the volume of PAE procedures will never come close to approaching the levels seen in adult patients. This leaves the small but growing field grappling with a question: How many pediatric advanced endoscopists does the country need, and what is the optimal training path for them?

Interest in PAE is definitely on the rise, so much so that in 2014, the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) established a special interest group focused on ERCP, which Dr. Liu chairs.

“Lack of interest is not a problem,” said Matthew Giefer, MD, the former chair of the NASPGHAN ERCP special interest group, who in 2019 left a longtime post at Seattle Children’s Hospital to establish a new PAE program at Ochsner Hospital for Children, in New Orleans. “Many gastroenterologists want to do this training, and institutions want to claim they have someone who does these cases, but the primary focus needs to be on how to safely meet the needs of the patients we serve.”

Unlike adult advanced endoscopy fellowships, which have a formal matching program sponsored by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, training opportunities for PAE are less formally organized. Two institutions, The University of Texas at San Antonio and CSMC, offer advanced endoscopy fellowships for pediatric gastroenterologists.

“They each train one a year and not every single year,” said Petar Mamula, MD, the director of the Kohl’s GI Nutrition and Diagnostic Center at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “It works for them because they have unique systems in their hospitals with combined pediatric and adult services. These are the only two programs I’m aware of where you can get this kind of training without begging your pediatric hospital to figure it out with a counterpart adult hospital, or otherwise arrange for you to be trained in an intense one-year program.”

A Wide Variety of Training Paths

Most pediatric advanced endoscopists practicing today received their training in an adult fellowship program. A new survey of practicing pediatric endoscopists within NASPGHAN, presented at the 2021 Digestive Disease Week (Pediatric Endoscopy Lecture, ID 3521190) illustrates the variability in training pathways. Of 41 endoscopists surveyed, 38 (92.7%) responded and 27 were included in the analysis because they were independently practicing either ERCP (n=23) or EUS (n=13). The majority of respondents (n=11) were trained either solely in an adult advanced endoscopy fellowship program (nine endoscopists) or with other additional modes of training (two endoscopists). Five additional respondents reported training solely with an adult advanced endoscopist, while seven others had training that included some time with adult advanced endoscopy. Two respondents had been specifically trained in a PAE fellowship program, while the remainder were trained in some other combination of these pathways.

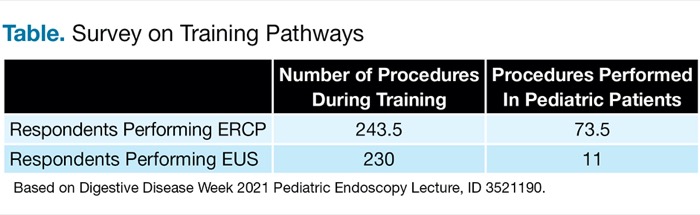

Most respondents performing ERCP (85.7%) and EUS (100%) reported that an adult advanced endoscopist was involved in their training, with less than half of respondents (46.4%) training with a pediatric advanced endoscopist, according to lead author Paul Tran, MD, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Children’s Hospital of Colorado, in Denver. Respondents performing ERCP completed a median of 243.5 of the procedures during training, with a minority performed in pediatric patients (73.5), Dr. Tran said. Those performing EUS reported completing a median of 230 EUS cases during training, with only 11 performed in pediatric patients (Table). Despite these low volumes, most respondents reported feeling prepared to practice pediatric ERCP (82%) and EUS (80%) independently upon completion of training.

| Table. Survey on Training Pathways | ||

| Number of Procedures During Training | Procedures Performed In Pediatric Patients | |

|---|---|---|

| Respondents Performing ERCP | 243.5 | 73.5 |

| Respondents Performing EUS | 230 | 11 |

| Based on Digestive Disease Week 2021 Pediatric Endoscopy Lecture, ID 3521190. | ||

Although “the training available for PAE has become more robust,” practitioners “have to really want to do this,” said Diana Lerner, MD, an associate professor of pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition at the Medical College of Wisconsin, in Milwaukee, and the chair of the NASPGHAN Endoscopy & Procedures Committee. “There is not a structured pathway for training the way there is in general pediatric GI or in adult advanced endoscopy. There are a few children’s hospitals in the country where adult sister hospitals have agreed to train pediatric endoscopists as a fourth-year fellowship coordinated between the pediatric and adult GI groups. We also need to consider that adult gastroenterologists are not trained to do endoscopy in children. And quality endoscopy is not about numbers, but competency. In reality, all new endoscopic procedures have to be learned in a post-fellowship manner for those who are already practicing in a procedural field.”

Jenifer Lightdale, MD, MPH, the division chief of pediatric gastroenterology at UMass Memorial Medical Center, in Worcester, and current president-elect of NASPGHAN, suggested that the advanced year in an adult program approach may be optimal for freestanding children’s hospitals. “You have your local adult group agree to take on a pediatric junior faculty member, someone who’s finished their fellowship and does an advanced year with an adult group that they can continue to be a part of, have as a resource, and also work with to maintain competency,” she said. “The pediatric endoscopist can go back to their freestanding pediatric center and practice independently, but they still have local mentors to reach out to just as they would as junior faculty anywhere.”

Questions About Workforce Size

The ideal number of endoscopists to make up the PAE workforce still needs to be determined, Dr. Mamula said. “How many do we need to train in the next five to 10 years? Young ambitious people who try to do this on their own may not be able to find a job. We are one of the largest pediatric hospitals in the country, with 6.5 thousand endoscopy procedures every single year, but we do about 50 to 60 pediatric ERCPs, which is barely a number good enough for me to maintain my skills,” he added.

“It’s hard to answer the question of what is the ideal workforce size and distribution for pediatric advanced endoscopy,” Dr. Giefer said, “but there honestly shouldn’t be someone doing this at every institution that treats pediatric GI disease, because many of them don’t have the volume to ensure they keep their expertise up.” There needs to be enough volume that endoscopists can maintain their competency, he stressed.

“When we think about these questions of workforce size and training, we first need to step back and ask what makes the best possible endoscopist,” said Monique Barakat, MD, an assistant professor of pediatrics (gastroenterology) and of medicine (gastroenterology and hepatology) at Lucile Packard Children’s Hospital Stanford, in Palo Alto, Calif., and lead author of the Pediatrics paper. “We know that ERCP is the highest-risk procedure that we perform, and that the more you do, the better your outcomes are going to be. So, we need to consider our training pathway in that context. Annually, I perform well over 250 ERCPs a year with my adult practice, and the volume threshold for maintenance of competency as a high-volume ERCP-performing endoscopist is around 100 to 200 ERCPs per year. If even well-trained pediatric advanced endoscopists aren’t approaching this annual volume threshold, even if they’re excellent and going through great training pathways, we may be doing them a disservice.”

But Dr. Lerner questioned that conclusion, citing a recent paper from Dr. Giefer and his colleagues (Surg Endosc 2015;29[12]:3543-3550). “Based on published data, even if pediatric endoscopists are not getting the same numbers of cases, their outcomes are showed to be equivalent,” she said. “We also must consider that if there is no pediatric endoscopist available to do pediatric ERCP, these procedures may become delayed and increase morbidity.”

Too Much, Yet Too Little

The demand for PAE is simultaneously “too much, yet too little,” Dr. Lerner said. “There’s enough demand that you need the skill sets, but the number of cases that happen annually at most pediatric facilities is not enough to reach the necessary competency numbers. It’s a really difficult situation, because then the children don’t have access to care without traveling a long way.”

The conundrum is a combination of numbers and location, Dr. Liu agreed. “If we have patients who are willing to travel across the country for these kinds of services, that shows that there is a need. I’m getting referrals from San Diego and I’m in Los Angeles, and I’ve known people in New York who needed an advanced endoscopist and were referred to someone in Boston,” he said. “There are places in the country where, if they lost an advanced endoscopist, they don’t have someone to fill that need.”

Dr. Barakat predicted that the path forward for PAE will probably be focused on a few centers of excellence around the country that have the volume necessary to maintain competence, with other programs relying on partnerships with adult practitioners.

In a survey she conducted of registered NASPGHAN programs, published in 2019, more than 90% of respondents reported performing fewer than 25 ERCPs annually and pediatric EUS was performed at less than half (47%) of respondents’ institutions (J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2019;69[1]:24-31).

“More than 70% of respondents believe their institution’s current arrangement for performing pediatric therapeutic endoscopy procedures is inadequate,” Dr. Barakat said. “Many of them felt that partnership with adult endoscopists was the way to go. Adult advanced endoscopists already perform a broad range of advanced procedures; could they become more comfortable with performing ERCPs for pediatric patients? I think we could normalize that this has to be part of the adult endoscopist’s responsibility and repertoire. There will be centers for excellence for highly complex pediatric cases, such as tiny neonates, but for bread-and-butter ERCPs, the adult endoscopists should be able to step in.”

That can be challenging, Dr. Lightdale said. “I recently had an email from someone at a big academic university hospital in a smaller state,” she said. “He had started out doing ERCPs at his local children’s hospital out of compassion but was feeling that even the infrequent times he was over there were costing him a lot in terms of time and productivity. We definitely need better partnerships between adult and pediatric groups, and perhaps more formal commitments to compensation for our adult colleagues who are helping us to care for children with their advanced endoscopy skills.”

Dr. Barakat acknowledged the issue: “I know a lot of my adult colleagues get nervous when they have a pediatric patient on the schedule. Part of that is the different way you communicate with children, and part is that pediatric ERCPs do tend to take a lot longer and have a lot more orchestration involved. That’s amplified if you don’t have a joint appointment within pediatric GI and are coming over from the adult side to assist. There’s an anxiety level, but these challenges are not insurmountable. And the life-year impact of a successful pediatric ERCP is tremendous. How many ERCPs would I need to do on 80- and 90-year-old patients to have the life-year impact of one ERCP on an 8-year-old? These pediatric ERCPs should be viewed as very special and important circumstances that all advanced endoscopists need to be mindful of.”

—Gina Shaw

The sources reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This article is from the September 2021 print issue.