For years, gastroenterologists have been aware that parenteral nutrition (PN), while lifesaving, can damage the liver. Now, researchers are beginning to gain an understanding of the underlying mechanisms in this complex process.

The gut responds and adapts to antigens and antibodies, and is constantly exposed to environmental toxins that challenge the barrier function, said Ajay Jain, MD, DNB, MHA, the associate division chief of pediatric gastroenterology, section head of pediatric nutrition and a professor of pediatrics at Saint Louis University, in Missouri, during a keynote address at the ASPEN 2021 Nutrition Science and Practice Conference.

“Enteral nutrients and trillions of bacteria modulate luminal targets along complicated signaling pathways, maintaining and challenging normal homeostasis,” Dr. Jain said. “The gut also serves as a major regulatory gateway controlling molecular trafficking, and seems intimately involved in systemic health and disease states via gut-systemic signaling.”

Strategically targeting gut–systemic cross talk “could bring a paradigm change in current therapeutics mitigating PN-associated injury, which remains a major research focus,” he said.

The interaction between farnesoid X receptor (FXR) and fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19) has been one area studied in how the gut regulates liver health in the context of PN, Dr. Jain said. FXR is thought to be present throughout the gut and particularly in the terminal ileum. As bile acids travel down from the gastrointestinal tract during regular food intake, they activate FXR, which results in the release of the metabolic hormone FGF19. This hormone then travels through the portal circulation to the liver and binds to its receptor, FGFR4. Another function of FGF19 is to regulate the enzyme CYP7A1, which is a rate-limited step in the synthesis of bile acid. In addition, FGF19 has been shown to regulate the homeostasis of lipids and blood sugar.

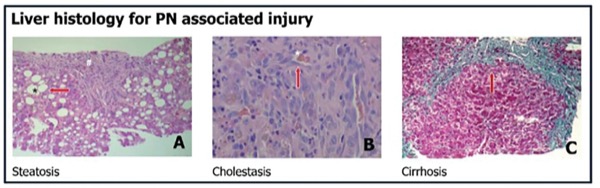

Parenteral feeding, which bypasses the gut, has been associated with complications of liver disease as well as atrophy of the gut mucosa and inflammation. The term intestinal failure–associated liver disease (IFALD)—hepatobiliary dysfunction secondary to intestinal failure—is increasingly used to describe PN-associated injury. Potential drivers of IFALD include prematurity, with premature infants’ immature hepatic transport and metabolism of bile acids partly contributing to injury. Additional drivers are toxicity of the PN solution, such as from lipids or other PN constituents like metals, which can impair hepatobiliary transporters, and sepsis, which can cause cytokine-mediated liver injury.

The Gut–Liver Connection

A novel idea that is being proposed is that the lack of luminal nutrients in patients on PN can disrupt bile acid and other signaling ligands along gut–systemic signaling pathways essential for health, Dr. Jain said. Indeed, IFALD has been shown to be minimal if enteral support can be provided. In the absence of enteral nutrition, gut FXR remains inactive, resulting in altered FGF19 signaling and liver disease. “Our gut feeling is that the gut really controls liver health during PN,” he said.

Dr. Jain’s laboratory has been studying this field for more than a decade. The researchers have created a novel ambulatory PN in piglets using miniature pumps and tunneled catheters. Comparing animals fed enteral nutrition, a PN diet, and PN plus enteral bile acids to activate gut–liver signaling, the group noted that enteral bile acids prevented hepatic injury, and both histologic and serologic liver injury markers were closer to those seen in the enteral feeding group (Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 2012;302[2]:G218-G224).

More recent studies in animals from his lab, and in humans from other labs, have demonstrated dramatic differences in gut microbiota between those fed enteral versus parenteral diets. Animals receiving enteral nutrition had a predominance of the Firmicutes phylum while those receiving PN had clonal shifts toward the Bacteroidetes phylum. Indeed, other studies have noted that humans with intestinal failure had an 18-fold overabundance of bacilli compared with healthy controls and lacked bacteria belonging to the Firmicutes phylum (JPEN 2017;41[2]:238-248).

Over the years, different components of PN therapy have been implicated in the development of IFALD in pediatric patients, said Jeffrey Rudolph, MD, the medical director of intestinal care and rehabilitation at UPMC Children’s Hospital, in Pittsburgh.

“What [Dr. Jain’s] talk really did was give insight into the complex interplay between the components of PN, the factors in the host recipient and even potentially the microbiome, and how that interplays all through FXR and FGF19 signaling,” Dr. Rudolph said.

Giving PN alone versus enteral nutrition seems to aggravate liver disease, Dr. Rudolph added, and Dr. Jain’s talk focused on the complex gut–liver axis that contributes to this process: “As a GI thinking about why it’s important to provide enteral nutrition, other than the idea of just weaning the PN, using nutrition as a therapeutic to help prevent liver disease and having some idea into the basic mechanisms of how that potentially works is very helpful and increased my understanding of how PN in IFALD is affected by things like sepsis, prematurity and other physiologic components of the host.”

—Karen Blum

Drs. Jain and Rudolph reported no relevant financial disclosures.

This article is from the August 2021 print issue.